It has been 53 years since Tang Da Wu’s first solo exhibition at the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry titled Drawings and Paintings. Upon Tang’s return to Singapore from his studies in 1979, he began to delve more into performance art, using his body as a medium to bring awareness to human beings’ relationship with nature, as well as the social and environmental issues that arose from urban development and transformation. From notable works like They Poach the Rhino, Chop Off His Horn and Make This Drink (1989) to Tiger’s Whip (1991), to Bumiputra(2005–06), Tang’s performances include installations, drawings and paintings. Sometimes all mediums are incorporated within a single work or exhibition, a physical manifestation of Tang’s firm belief that “an artist should introduce to others what he sees or learns of something.”

The performing medium and its materials – a brief look back

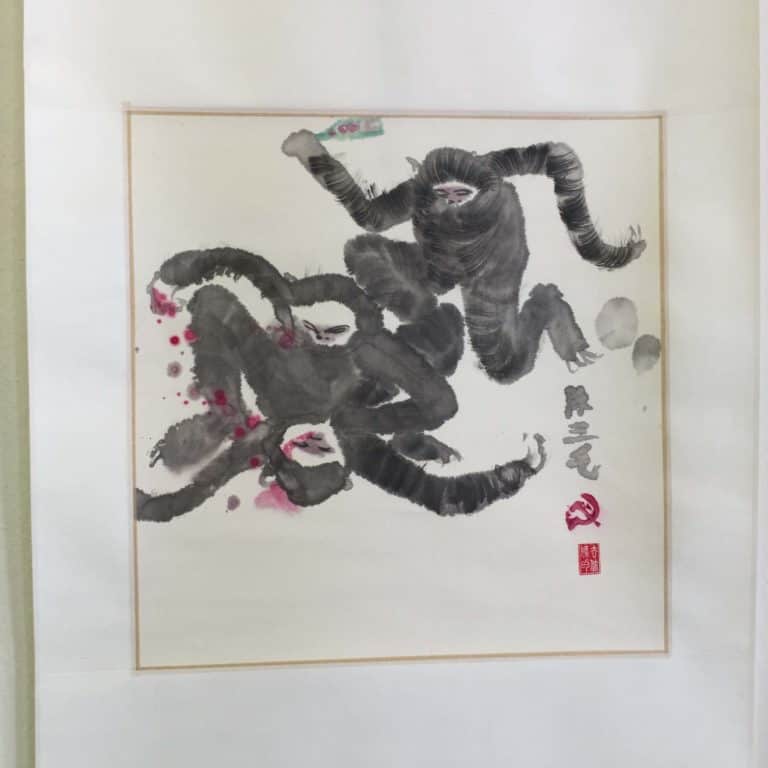

At the mention of Tang’s name, his seminal 1991 performance immediately springs into my mind. More than 30 years since the original performance took place, I recall my first encounter with the post-installation piece of Tiger’s Whip as an art student at National Gallery Singapore. It featured a tiger standing on its hind legs, with its front paws resting on a rocking chair draped in a red cloth –remnants from the live performance conducted many years before in Chinatown.

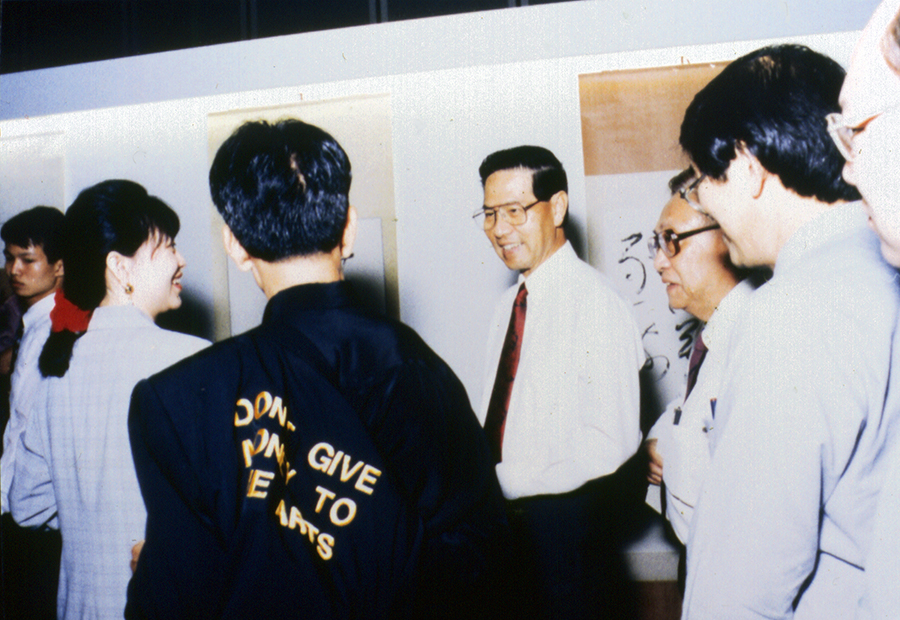

Don’t Give Money to the Arts (1995) was another significant performance piece that highlights the artist’s discipline and criticality in the mediums he uses for each work. The only tangible materials produced for this performance were a black jacket with the words ‘Don’t Give Money to the Arts’ embroidered in gold at the back, and a note that said, ‘I am an artist. I am important.’

Performed during the opening night of Singapore Art ’95, an art event in 1995, the act took place during a time when performance art was prohibited by the Singapore authorities. No less than the then-President of Singapore himself (Mr Ong Teng Cheong) was intentionally implicated in the work. Tang asked for his permission to wear the jacket and handed him the note after permission was granted. Meant to showcase artists’ wit and ability to evade prohibitions on artistic expression, the work also prompted questions on the true value of art and its quantification.

Beyond beauty

Amidst the infinite amount of visual stimuli fighting for our attention, how does art stand out from the crowd when it is not placed within a gallery space, or filled with immediately aesthetically pleasing qualities?

Tang tackles this dilemma by creating sculptures and installations that trigger more than just momentary reflection. Whether it is in their very materiality or through the incorporation of strong cultural symbols and imagery, both the intangible and tangible aspects of his work count on recognition and deep association on the part of the audience. As his famous saying goes, an artist’s works should provoke the mind and “should provide thoughts not [just] to please the eyes or to entertain.”

3, 4, 5, I Don’t Like Fine Art

Another thing that is hard to ignore is the way that Tang titles his works, and his latest solo show Shanghart in Gillman Barracks is no different. Coming from an artist with a practice that spans more than half a century, the exhibition title 3, 4, 5, I Don’t Like Fine Art immediately caught my attention.

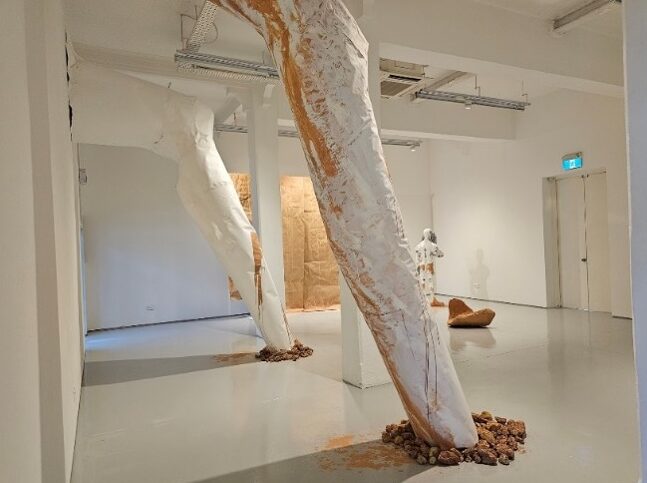

Upon stepping through the gallery doors at Shanghart, I was greeted with a life-sized plaster door covered in terracotta brown, and its presence put an abrupt pause in my step. Regaining my rhythm, I made my way around the sculpture and found numerous installations of various scales and mediums, that existed in harmony within the small gallery space in a consistent white and brown colour palette.

I was first drawn to the sculpture She Asked the Forest for a Moment of Stillness, which featured logs that fitted perfectly and naturally into one another, despite being of different thicknesses and lengths. They were arranged on top of a bird-like creature with mirrored geometric shapes lying beneath.

Undeniably, these elements recalled Tang’s Sembawang Phoenix (2013), a sculpture that represented the long tailed nightjar (colloquially known as the ‘tok-tok bird’) that was exhibited at the Singapore Art Museum ten years ago. The mixed media artwork was a part of a larger installation that expressed the artist’s memories, impressions and mythologisation of Sembawang – the original home of The Artists Village founded by Tang himself in 1988. With these connecting strands and associations, it became clear to me that 3, 4, 5 I Don’t Like Fine Art was a continuation of that process.

Moving away from animalistic forms, Mud Legs was a sculpture made of two towering pipe-like structures of paper and splashes of nude paint. A bed of rocks was placed at the base of each ‘leg.’ When looked at from afar, the rocks seemed to take on the texture of thick, cakey mud that lumps up when a foreign solid object enters viscous liquid. What struck me about Mud Legs was how the large 4-metre bent columns were made entirely out of paper.

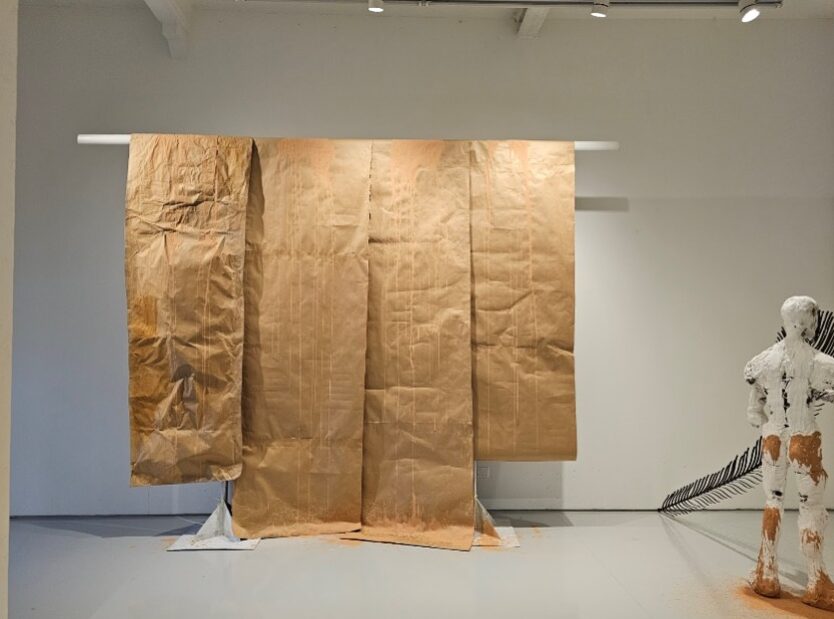

More brown- on -brown paper canvases occupied the wall at the other end of the gallery space, draped like curtains. I felt like I could spend the whole day allowing my eyes to wander around and appreciate the textures formed by creases in the paper, and the subtle shades and tones of actual earth pigment on brown paper. Here, Tang shows viewers that something we regard as mundane and even dirty, can be used to create delicate beauty.

This raw aesthetic also seemed to reflect Tang’s continued resistance against creating polished and ‘finished’ works of art, a sense of cheeky defiance when thought of alongside the title of the show. It reminded me of Gully Curtains(1979) and the comment he had received from the director of the National Museum Art Gallery where the work was exhibited, who exhorted that “earth and lumps of clay shouldn’t be in the museum.”

What kind of materials do belong in a museum, and who makes these decisions of inclusion and exclusion? It is this invisible criteria of what defines ‘fine art in a museum’ that artists like Tang are trying to challenge, offering a counter to what fine art is expected to be.

The bird motif is revisited once again through a white plaster figure that stands facing the corner of the gallery on the right, whilst holding on to a large metal bird feather. The figure represents Tang himself doing a taichi pose called ‘grasp the bird’s tail’. The metal feather is meant to resemble the tail of the ‘tok-tok bird’ that Tang had often encountered at night during his stay at The Artists Village, amongst other animals.

On the opening night of the show, Tang painted in the gallery, live, using earth.

One of the final results, produced as a huge crowd watched on, was an image of a snake strangling a boat, plastered onto the gallery wall. Situated alongside it was a sculpture composed of what looked like pieces of driftwood, put together with small wooden planks and nails.

In the corner of the same room were several aluminium mesh pillars with paper structures stacked onto some of them, once again stained with a muddy colourant.

The paper structures here seemed to take on the silhouette of the drains that line the streets of Singapore– the narrow, shallow ones that usually run alongside concrete pavements. It was an abstract nod to the more quotidian aspects of our city’s architecture, instantly recognisable to its dwellers without being overly – prescriptive or literal.

What Tang Da Wu’s art did to me

True to the artist’s intent, I found Tang’s sculptures and installations to be much more than just aesthetically pleasing to me. His creations were visually engaging in a plain and simple way that made the work feel accessible and easy to connect with. I could see what he saw, and felt what he felt – the memories of a place he held dear and the spirit of fun and creative expression associated with those memories.

For me, art is powerful because of its ability to first catch your attention, and then hold it long enough for thought and reflection to take place. Whether that means creating fleeting performance pieces with strong messages about social and environmental issues, or nostalgic sculptures that reflect upon the loss of spaces, Tang’s conscious use of mediums and materials stood out to me as his biggest strength as an artist. My biggest takeaway as an artist myself who is still fine tuning my own visual language? Be precise and intentional, but also remember to play.

___________________________________________

3, 4, 5, I Don’t Like Fine Art by Tang Da Wu is on view at Shanghart Singapore till 1 October.