If you’ve ever been met with dead silence after re-telling a joke in another language, you’ll know that translation is a tricky business. Words lose their zest, sneaky subtexts are sapped dry, and an entire sentence easily falls flat in the hands of an inexpert interpreter. But in the hands of the right folks, the tricky process of mediating between languages and cultures can be enormously productive. Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez famously declared that Gregory Rabassa’s English translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude was better than the Spanish original. “A good translation is always a re-creation in another language,” says García Márquez.

How is translation a creative act? What do we gain and lose through processes of cross-cultural exchange? And, conversely, what can we learn from errors in translation? These are just some of the questions that the Institutum’s ongoing exhibition, Translations: Afro-Asian Poetics, asks us to ponder.

Curated by Zoé Whitley with assistance from Clara Che Wei Peh, the exhibition unfurls across five galleries at Gillman Barracks. It features about a hundred artists from African and Asian diasporas, many of them international heavyweights like Yinka Shonibare and Haegue Yang. Whitley’s resume is no less impressive: she has held curatorial roles at the Tate, Hayward Gallery, and the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2019), and is currently director of Chisenhale Gallery.

Translations is a show with big ambitions. Stepping away from the biennale model which organises artists by nationality, the exhibition traces criss-crossing currents of artistic styles, techniques, and ideas between the African and Asian diasporas, “two vast but interconnected cultures with distinctive, multilingual rhythms and modes of expression.”

“Any museum that celebrates world cultures may have African art in one wing and Asian art in another,” Dr. Whitley explains. But here, silkscreened photographs by the Gambian-British artist Khadija Saye, for instance, hang facing a ceramic fertility jar by the Mumbai-born and Singapore-based artist Madhvi Subrahmanian.

Like a number of recent exhibitions and programmes in Singapore, Translations takes on the project of fostering “South-South conversations.” From T:>Works’s Per°Form Open Academy of Arts and Activations, to the National Gallery Singapore’s ongoing exhibition Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, curators and audiences have been turning to formerly marginalised regions in search of diverse voices.

Rather than set forth how the imperial centres of the Global North have “influenced” art in the peripheral colonies of the Global South—as conventional art history has often done—Translations spotlights exchanges between diasporic communities who share histories of movement and migration, and “erod[es] the constructed barriers across geography and race.”

At the same time, however, Dr. Whitley notes that: “None of the connective threads or tissues in this exhibition are about a literal saying that this culture is like this other culture. There’s no interest in flattening. If anything, we want to ruffle things as much as possible.”

In line with this “ruffling,” the curators have done away with the sort of structured interpretative framework we might expect of a museum exhibition (extensive wall texts, captions, and thematic section dividers). Instead, poetry translated from oral and vernacular traditions around the world, including the Malay pantun, the Japanese haiku, the African-American eintou, and the Swahili ushairi, are printed on the walls, echoing the thematic issues that emerge across the exhibits.

Finding a place, becoming visible

The idea of home, for one, threads through several of the galleries. Illuminated within a glassy box-like pedestal is Doh Ho Suh’s life-sized fabric reproduction of a stove from a former apartment in New York City. Nearby, Sumakshi Singh’s delicate thread installation Staircase to the First Floor (2023) similarly evokes the uncertainty of transitional spaces—the sense of being neither here nor there, uprooted in processes of migration. These ghostly, forlorn silhouettes of architecture and domestic fixtures speak to how experiences of belonging and identity are woven into our everyday living spaces.

In the same gallery is a 2-channel video work by Tuan Andrew Nguyen which similarly explores diasporic experiences of the built environment. Because No One Living Will Listen (2023) centres on a speculative letter written by Habiba, the daughter of a Moroccan soldier who defected from the French army while combating anticolonial uprisings in Vietnam during the First Indochina War. The video centres on the Moroccan Gate, a monument built by Moroccans in Hanoi in the 1950s, symbolising shared ties and a mutual history of resistance.

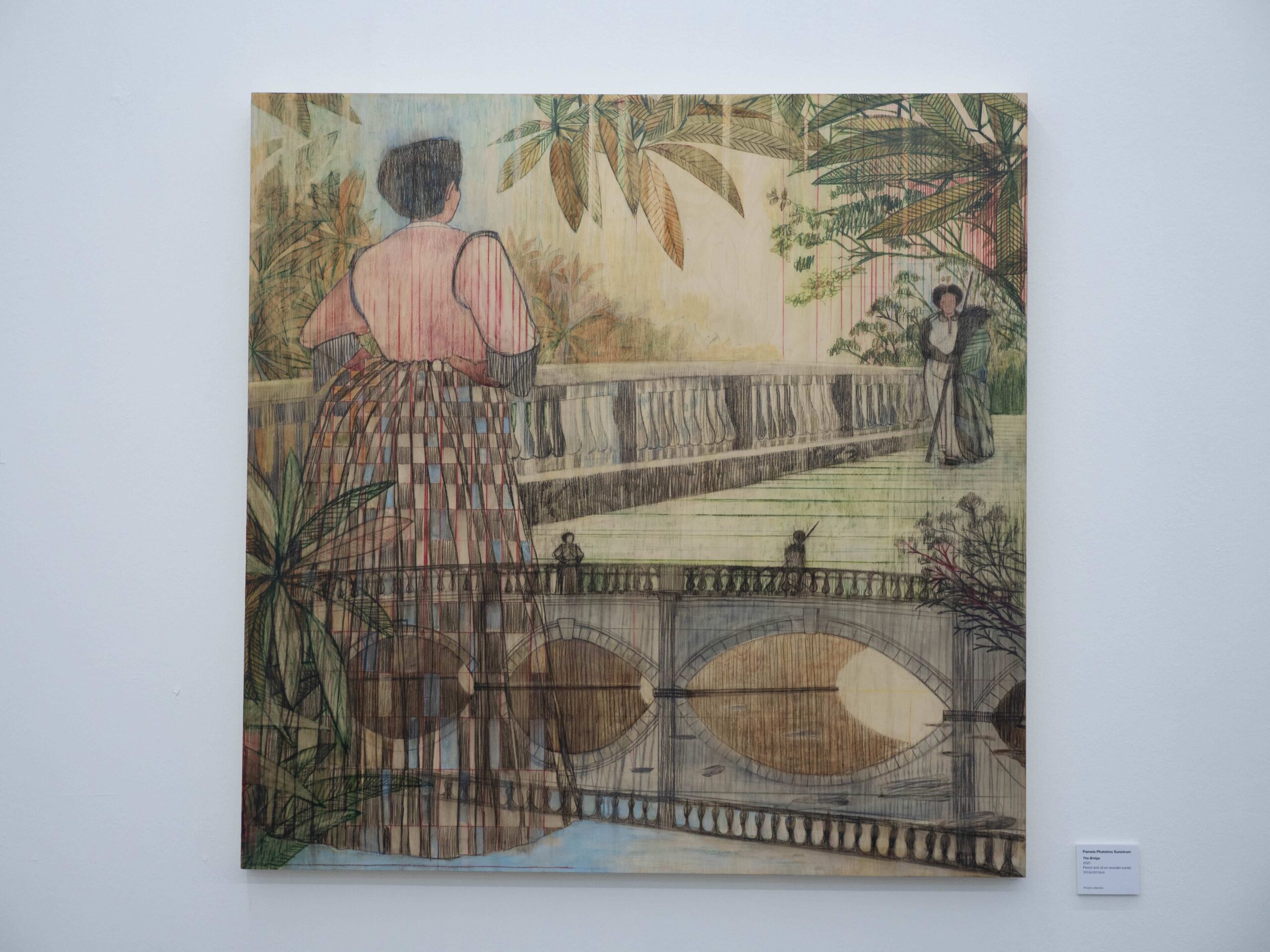

Such allusions to political histories of oppression are unavoidably present in the show, though often in an implicit fashion. In The Bridge (2021), Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum reimagines what Black women in the 19th century who were excluded from the grand tradition of oil on canvas might’ve looked like. Two women—well-to-do, from the looks of their clothing—meet on a bridge with a vaguely neo-classical balustrade.

The figure in the background, however, is faceless, while the one in the foreground has her back turned against us. Her vividly patterned skirt floats over a plant with broad, long leaves, while the vertical grain of the wooden panel cuts through their bodies, rendering them translucent. The work seems to ask: How can painting re-assert the presence of a people who have been made invisible and excluded from history? Through a deceptively straightforward, genteel painting, Sunstrum stakes her claim to representational visibility.

Craftsmanship and tradition

Such negotiations of multiple artistic traditions recur throughout the show. Theaster Gates’s sculptural installation Afro-Ikebana (2019) juxtaposes a bronze sculpture of an African mask with stacked tatami mats and a bamboo shoot in a ceramic vessel. The Chicago-born artist works at the intersection of African-American and Japanese aesthetics. Gates calls his creative philosophy “Afro-Mingei,” combining the term for the natural hairstyle that became an important symbol of Black identity and empowerment in the 1960s with the Japanese concept of mingei, developed by a group of craftsmen and philosophers who celebrated the simplicity and authenticity of the folk arts.

A ruby and a mango shoot;

A tiny catfish on my palm!

The world is one, tho’ far to boot;

When out of sight, keep memory warm.

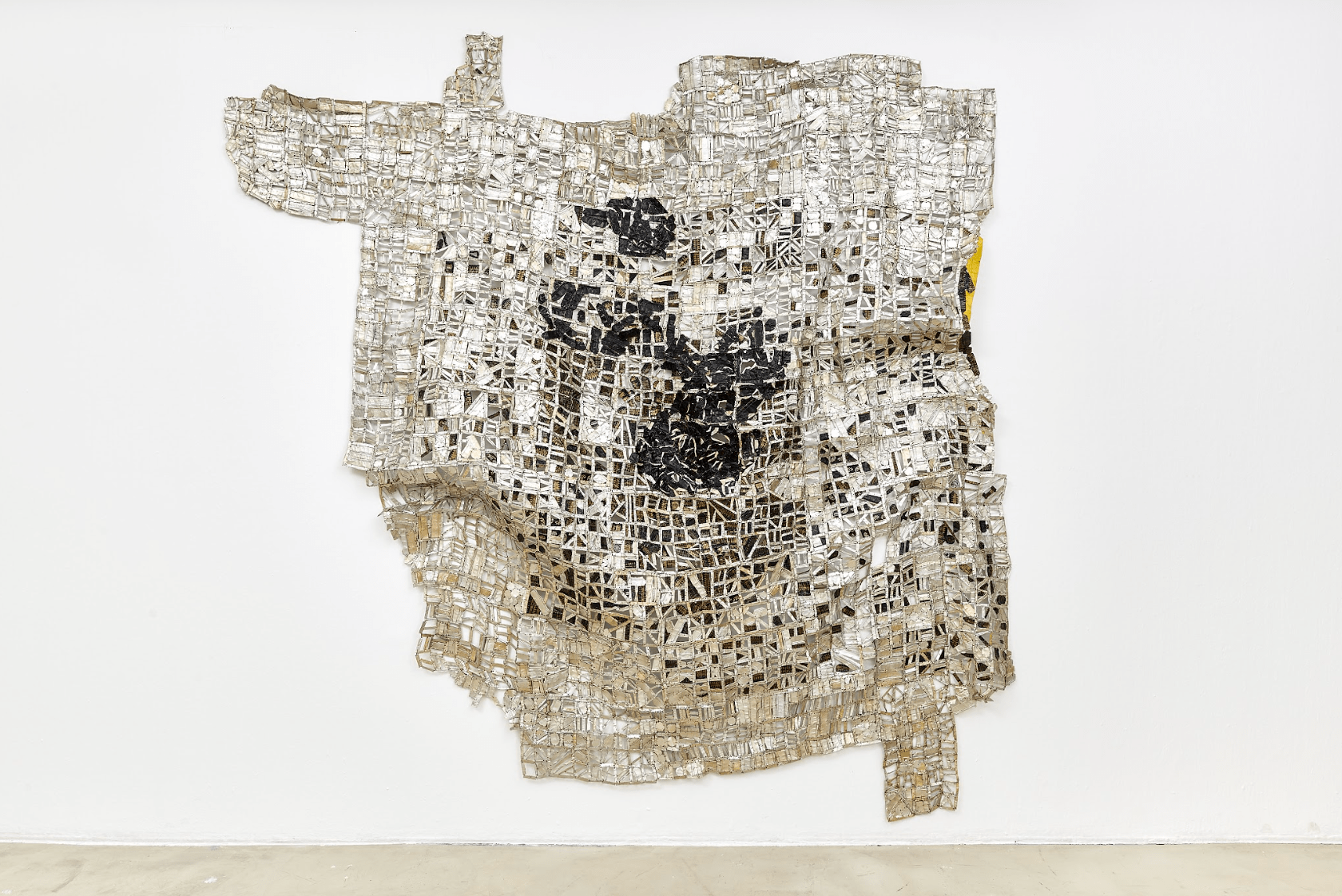

Translated from a Malay pantun, this passage frames the works exhibited at ShanghART Gallery, which foreground ecological issues. The centrepiece of this segment is Tse (2016), a shimmery, undulating wall hanging assembled out of discarded labels, caps, and bottle wrappers by the acclaimed Ghanian artist El Anatsui. Dark patches coalesce towards the centre of the sculpture, evoking an oil spill floating on the sea’s surface.

Anatsui’s silvery sculpture hangs next to a blue one by Ari Bayuaji. With its almost silky sheen, it’s hard to tell from afar what Bayuaji’s patchwork-like tapestry is made of. But look closer and you’ll notice tiny knots in the work which bear witness to the laborious process by which it was created.

The Old Sail #2 (2021) consists of discarded plastic ropes, which the artist and his collaborators collected from mangrove forests and beaches, unravelled by hand, and knotted together to create fine threads for weaving. Using traditional Balinese techniques, Bayuaji’s “sail” activates craftsmanship in tackling the twin issues of waste and environmental pollution.

Apart from craft, Translations also looks at performance as an expression of cultural tradition. In Vibha Galhotra’s Altering (2021), what looks at first glance like a cluster of trees reflected in water turns out to be a sculpture amassed from tiny silver, gold, and black bells. These bells, known as ghungroos, are typically tied to the ankles of classical Indian dancers, accentuating the sounds of their complex footwork.

Galhorta’s wall sculpture is displayed next to Nick Cave’s Soundsuit (2010), a fantastical garment festooned with sequins. Like the ghungroos, the plastic buttons attached to the back of the suit with plastic tags create a musical rattle when the suit is worn. The vivid colours and joyful musicality of Cave’s and Galhotra’s works suggest unexpected resonances across cultures of the Global South that might seem entirely different at first glance.

More importantly, Soundsuit also reminds us that engaging with cultural “others”—people who look and live differently than we do—may sometimes require us to confront difficult histories of prejudice and violence. Cave, a multimedia artist and performer, first began making his Soundsuits in 1991, after the Los Angeles police’s racial profiling and beating of Rodney King, an African-American man, caused a public uproar. Cave envisioned the Soundsuits as a protective “second skin” that masked a person’s identity, shielding them from the violence of racial, class, and gender inequality.

Some closing thoughts

A commitment to the discourses of the Global South—found in Translations and other exhibitions and projects alike—is, I think, a welcome shift, one which sees art as a means of building unexpected solidarities between geographically distant cultures. It also moves away from Eurocentric notions of artistic “influence” in which art made anywhere else is regarded as a bastardisation or offshoot of ideas and movements which began in Paris or New York.

Crucially, Translations stresses not just the authority of “the source text”—each style or technique’s culture of origin, so to speak—but also the agency of the interpreter. For instance, Ogawa Machiko’s raw, earthy vessels demonstrate how West African ceramic traditions might be re-interpreted by an artist trained in Japanese techniques. Similarly, Yinka Shonibare stresses how the bright, colourful “African” fabrics and patterns in his work were first produced by the Dutch based on Indonesian traditions, before being copied by English manufacturers and sold in West Africa.

As the show engages with issues (migration, ecological crisis, the politics of representation and visibility) that affect the African and Asian diasporas, it also reminds us of the fluidity and constructed nature of identity, celebrating the hybrid and in-between.

And what’s especially laudable about Translations is that it approaches these complex issues not through chunks of theory-laden artspeak, but through the sheer visual impact of the works themselves — which reveal thematic resonances through similarities in style or shared material techniques. The show’s considered curation leaves space for nuances to emerge, while weaving together a coherent experience for the viewer.

If there’s one gripe I have with this remarkably conceived exhibition, it’s that the omission of artwork descriptions—while entirely in line with the curators’ intention to leave the works open to subjective, “poetic” interpretation—might make it difficult for audiences to engage the works’ often complex contexts.

But as I catch myself asking for more overt curatorial guidance, I also wonder if we audiences in Singapore might be a little too used to being told what to think about a work of art, a little too quick to skim over works that don’t yield their nuances upon first glance. Many of the works in Translations are really quite something, and certainly they merit longer looking and more thoughtful engagement on the viewer’s part. It’s a show that’s definitely worth seeing this Art Week—catch it if you can.

_______________________________

Translations: Afro-Asian Poetics runs through 30 January 2024 across multiple sites at Gillman Barracks and Nouri. Opening hours Monday to Sunday, 11am–6pm. Visit the Institutum website to learn more.

Header image: Exhibition view of Translations: Afro-Asian Poetics. Images courtesy of the author unless otherwise stated.