If you had to hazard a guess on what Singapore’s favourite national pastime is, what would your answer be?

Eating?

Shopping?

You’d probably be right.

However, with Singapore recently boasting “one of the world’s highest per capita cinema attendance rates at around 4.2 visits per person per year,” we’d take a punt that movie-going ranks right up there, as one of our favourite things to do.

It’s part of a date night, it’s the end-of-term ritual after the last school exam, it’s a fun family day out that can appeal to the kids and old folks alike, it’s an excuse to feast on butter-drenched popcorn (you’ll find the best at Shaw Lido – trust us on this), it’s a corporate event with wide mass appeal… the list goes on and on.

The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) keeps its finger on the pulse of this particular cultural vein with its present exhibition Cinerama, which, “brings together 10 artists and collectives from across Southeast Asia who work through the medium of the moving image to explore its history, current-day expressions, and potential for the future.”

That’s a lot of words for an innocuous everyday pastime, so here’s a brief list of our favourite artworks, based on different types of movie categories:

1) The Action- Adventure

Forget Rambo, Indiana Jones and their macho action-hero brethren, the true stars of The Propeller Group’s works AK-47 vs. M16 and AK-47 vs. M16, The Film are the bullets and guns of action movies. AK-47 vs. M16 is a single-channel video work that shows the trajectory of bullets as they tear their way through ballistic gel which is meant to replicate human flesh.

The collision is quite beautiful, in a shiny, silvery cosmic way. Some gorgeous patterns emerge as the bullets make their way towards each other:

The works also recall ironic pop culture references to 1980s Hollywood action movies which almost always borrowed themes from the Cold War. The AK-47 was, of course, an assault rifle famously invented by Mikhail Kalashnikov and has even been described as “a true cultural brand of Russia”. The M-16, by contrast, is an American creation and has been used in the US military for decades.

Does anyone remember Rocky IV?

Look at the AK-47 vs. M16 works, and you can practically hear the opening bars of Burning Heart:

The works are also particularly resonant for what they omit.

AK-47 vs. M16 depicts a simulation of bullets tearing through a body, but without the blood and mess of actual flesh. AK-47 vs. M16, The Film is a pastiche of clips from different action movies, but without their human protagonists, as it is the weapons which take centre stage. The absence of human characters creates an unnatural vacuum, creating a sense of discomfort that perhaps mirrors the problematic situation when people become desensitised to violence. Such absence also provides an interesting counterpoint to the exhortations of the American anti-gun-control lobby – that “guns don’t kill people, people kill people.”

Framing all of these narratives is the quiet fact of where The Propeller Group actually hails from – Vietnam – a country which is painfully familiar with the battles fought between the AK-47 and M-16. With that subtle connection, the shiny Hollywood bubble dissolves, only to re-form as something far closer to home and far grimmer.

2) The Cartoon Musical

From macho theatrics, we move on to Narpati Awangga’s (a.k.a Oomleo’s) PAC-MAN- like video installation Maze Out (2017). It’s a compilation of his pixel art images made since the early 2000s and is assembled in a manner that recalls video arcade games of the 1980s.

SAM curator Tan Siuli observes that “pixel art’s simplicity and accessibility allows amateurs and professionals alike endless possibilities for creating new art through reuse and recycling.” Oomleo’s pixels in particular draw inspiration from Indonesian life, depicting his friends and “certain observable stereotypes in Indonesian society (for instance, the fitness fanatic who takes to jogging in Jakarta traffic).”

There is an interactive component of this work which allows visitors to paste stickers of the pixellated images on the walls of the room, extending the artworks beyond the confines of the animated video.

3) The Silent Movie

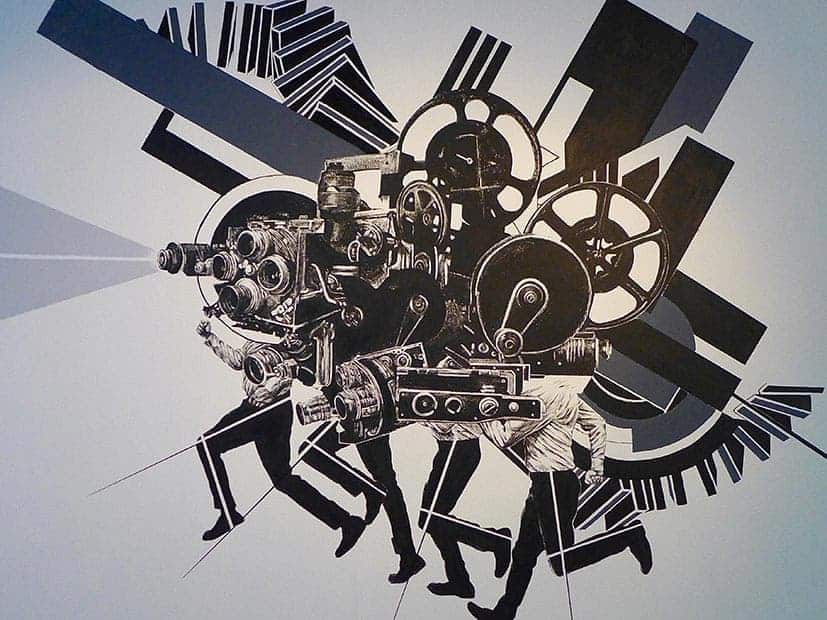

The first thing that pops out in Victor Balanon’s The Man Who is its trippy wall mural of what appears to be disembodied legs, running off into the distance with film equipment. Has the equipment grown legs? Have the people turned into technical gear? Where does the person begin, and the machine end?

This melding of man and machine into one ceaselessly running entity is a clever tribute to Balanon’s professional roots as a junior animator in a Japanese studio, where he was required to practice the same basic “running man” animation technique, repeatedly. It is a salute to the faceless, nameless employees who conduct all aspects of animation work behind the scenes. SAM curator Joyce Toh describes Balanon himself as “‘a man who’ was amongst the anonymous many who produced the innumerable hand-drawn illustrations required for an animation.”

4) The Foreign Film

SAM curators have to be applauded for the psychedelic presentation of Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic’s work There’s a word I’m trying to remember, for a feeling I’m about to have (a distracted path towards extinction). While the film is screened, you sit in a darkened room, on pillows set on the ground, which have been laid over compacted earth, dotted with random found objects. The whole thing feels like you’re watching a film under the stars, or out in space.

And what a film it is!

Post-apocalyptic images are spliced against scenes from a wedding celebration, creating a disturbing (yet quite lovely) juxtaposition. As with most art films, we’d suggest you not over-think it too much – just step into the space, enjoy the air conditioning and allow the images and atmosphere to wash over you and draw you in.

5) The Nod to Film Noir

Ming Wong’s Making Chinatown (2012) is a bundle of fun to interact with. Crafted as a response to Roman Polanski’s 1974 film “Chinatown,” the artist recreates scenes from the movie except that he personally takes on every role, to hilarious effect. The scenes are filmed against backdrops which are printed with stills from the actual movie, allowing Wong to literally imprint his own interpretations onto the classic film.

Curator Tan Siuli explains that the videos are then “projected onto the wooden screens they were filmed against, while the gallery is transformed into an immersive space resembling a studio backlot, emphasising its makeshift and malleable quality, and the artifice of cinematic production.”

The movie Chinatown has been described as the “best film of all time,” and in spite of its titular appropriation of notions of Asian diasporic communities, appears to feature no such Asians in its main cast. Wong hilariously claims a space for himself in this Western classic, taking cinematic tokenism to its ridiculous extremes as he turns the entire cast of Chinatown into an Asian one-man show.

The satire reminded us of this excellent video which provides a great introduction on why we so rarely see Asian leading men on the silver screen:

We loved Wong’s gumption! In re-framing Hollywood’s narratives from an Asian perspective, he’s managed to oh-so-elegantly thumb his nose at pre-existing stereotypes and prejudices.

Cinerama is presently at the tail end of its run, so catch it soon at the Singapore Art Museum before the show closes on 25 March.