What counts as art — and who decides? For decades, the answer seemed obvious: oil paintings and marble sculptures displayed in white-walled galleries, or one-of-a-kind works sold at champagne-soaked art fairs. Yet step into Singapore’s pop culture conventions today and that definition begins to blur. Here, the “art fair” is a vibrant, hyper-popular affair where the most coveted pieces might be digital prints, keychains, or stickers, and where creators often meet their audiences face-to-face across a folding table, rather than through a gallerist.

A buzz of excitement fills the air-conditioned halls, where rows of artworks stretch into the distance. In place of canvases, poster prints, many digitally rendered, line the booths, and tables overflow with charms and stickers. The subject matter, too, is worlds apart from the usual fine-art offerings, ranging from comic book characters to kawaii Japanese mascots. Cosplayers in elaborate Lolita dresses and mecha suits mingle with artists lugging suitcases of their work and youths flaunting transparent tote bags stuffed with beloved merch.

This is the lively, youth-driven world of fandom and artist conventions. Stalwarts like Doujin Market and the Illustration Arts Festival have wrapped for the year, while Anime Festival Asia and the End of Year J-Culture Festival are still to come. With newer names such as mARTsuri, DOKI! DOKI! Anime Market, and Art Riot ensuring that the next fair is never too far away, this once-niche scene is clearly here to stay.

For many, these spaces still sit outside the conventional idea of the art world — they’re seen as too commercial, too derivative, too playful to be considered “serious.” Yet such criticisms echo older debates about photography, printmaking, and even street art — all of which were once excluded from the category of “real art” before being embraced by museums and collectors. And like those once-dismissed forms, pop art conventions are proving that public appetite tells a different story.

Despite such criticisms, the crowds flocking to pop art conventions suggest that demand rivals that of fine art fairs. Many artists here, too, have built loyal followings of repeat collectors, blurring the line between fandom and patronage.

Artists like Sheryl Meyyen and Elizabeth The Severe, for example, have gained a devoted following with their dreamy portraits of vampiric pretty boys. As with many convention artists, their work is deeply personal — even when it ventures into fanart. “I make a lot of self-indulgent art,” Elizabeth says. “I’ll draw whatever makes me happy … Life is already hard, I don’t want to stress myself out over making art.”

For Meyyen, the most rewarding part is the community built with “likeminded individuals” who have “been nothing but supportive” — a connection that feels “more personal and meaningful” than simply having fans.

One difference between pop culture conventions and more established art events lies, perhaps, in tone. Conventions are often youth-driven and informal, with fanart — art inspired by existing media — still struggling to claim the same cultural legitimacy as fine art. Yet, as history shows, many artists first hone their skills by responding to the works that inspire them.

This diversity of practice is another sign of how conventions expand the boundaries of what art can be. They draw not only illustrators but also artists from other fields. Tattoo artists Charlie Mae and Nat, as well as illustrator Michael Pain, who also performs as drag king Laddie Oscar Wild, use these events to experiment with work outside their usual mediums and connect with potential clients. They share that such opportunities help them diversify their practices and make their art more accessible to a wider audience.

The exchange goes both ways: convention-based artists can also find new audiences beyond the scene. Kenneth Chin, for example, has seen his nature-inspired prints and merchandise attract the attention of organisations like Mandai Wildlife Group and NParks, leading to commissions for infographics and murals.

These cases underscore how conventions are not just alternative marketplaces but also fertile grounds for cross-pollination, where artists test new mediums, reach new audiences, and reconsider what their practices can be.

If traditional fairs prioritise exclusivity — with gallerists, press previews and VIP openings mediating access — conventions offer immediacy and accessibility. Artist and audience meet directly across a booth, collapsing hierarchies and fostering a sense of shared enthusiasm. It’s a model of connection rooted less in status and more in community — and it’s no less valid as a way of sustaining an art ecosystem.

The ways these connections are forged may differ, but both art fairs and pop culture conventions serve a similar purpose: they bring together artists and audiences from around the world. At first glance, the contrasts between the two are striking — pop conventions often prioritise affordable, mass-produced prints and trinkets, while art fairs highlight one-of-a-kind paintings and sculptures, including works by artists long deceased whose legacies endure.

Yet the boundaries blur here too. Photography and fine art prints, often offered as more accessible alternatives to rarefied originals, are a staple of many art fairs. Some are even sold as limited editions, coveted by collectors much like merchandise runs at conventions. Critics argue that reproductions dilute the value of art, but audiences tell a different story. Whether at a convention or a fair, buyers are eager to take home pieces that resonate with them — and in some cases, owning the same work as others can strengthen the sense of community that underpins convention culture.

The overlap extends beyond objects to audiences themselves. Visitors frequently cross between both types of events, especially when art fairs are part of larger cultural festivals like ART SG during Singapore Art Week, or when conventions spotlight original works, as seen in July’s Illustration Arts Festival. All of this suggests that the boundary between “high” art and “fan” art is more porous than it might seem — and that the question of what counts as art is as much about how people connect with it as it is about how it’s made.

Perhaps, then, the most telling insight is not in tallying the differences and similarities between art fairs and pop culture conventions, but in recognising how both speak to art’s evolving purpose. Conventions offer a platform for young creators to express themselves, experiment, and find their audiences — much as art fairs once did for generations before them.

Art has never been static, nor confined to gilded frames and white-cube galleries. It has always adapted to new technologies, new communities, and new ways of seeing. As keychains, fanart prints, and digital illustrations draw crowds as fervent as those for oil paintings and sculptures, the question “What counts as art?” may not have a fixed answer — and that, perhaps, is precisely the point.

___________________________________

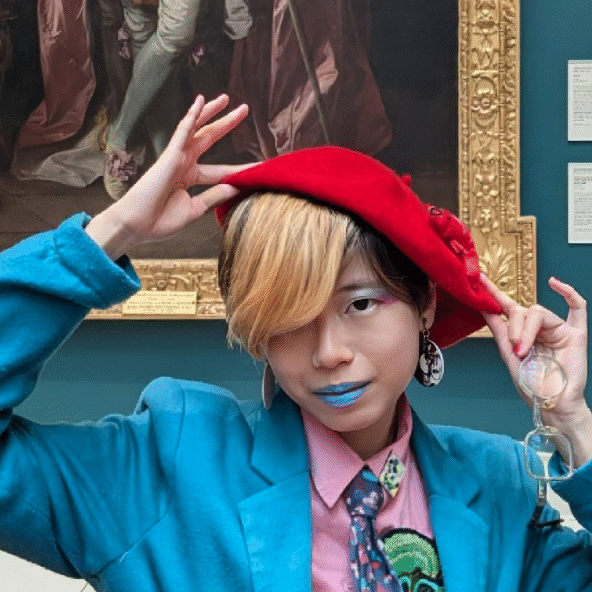

Header image: An exhibitor and patron at a self-decorated stall at Doujin Market 2025. Image courtesy of Neo Tokyo Project.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When Art Becomes Script: T:>Works’ 24-Hour Playwriting Competition at the National Gallery Singapore

Solamalay Namasivayam: Singapore’s Unacknowledged Master of the Nude

What is Creative Technology? A Curator’s Thoughts on Media, Art, and Design