He pioneered life figure drawing in Singapore, introducing it into the curriculum at the LASALLE College of the Arts in 1987. Singapore’s foremost art historian T. K. Sabapathy commented that his works were “the outstanding works” in a 1991 group show devoted to the human figure and nude form. His artistic trajectory, from art teacher to full-time artist, even mirrors that of the much-feted Singaporean Chinese painter Lim Tze Peng, who’s been celebrated as a titan of Singapore’s art scene. Despite all of this, Singaporean artist Solamalay Namasivayam (1926–2013) never received significant recognition as a pioneering artist during his lifetime. Why?

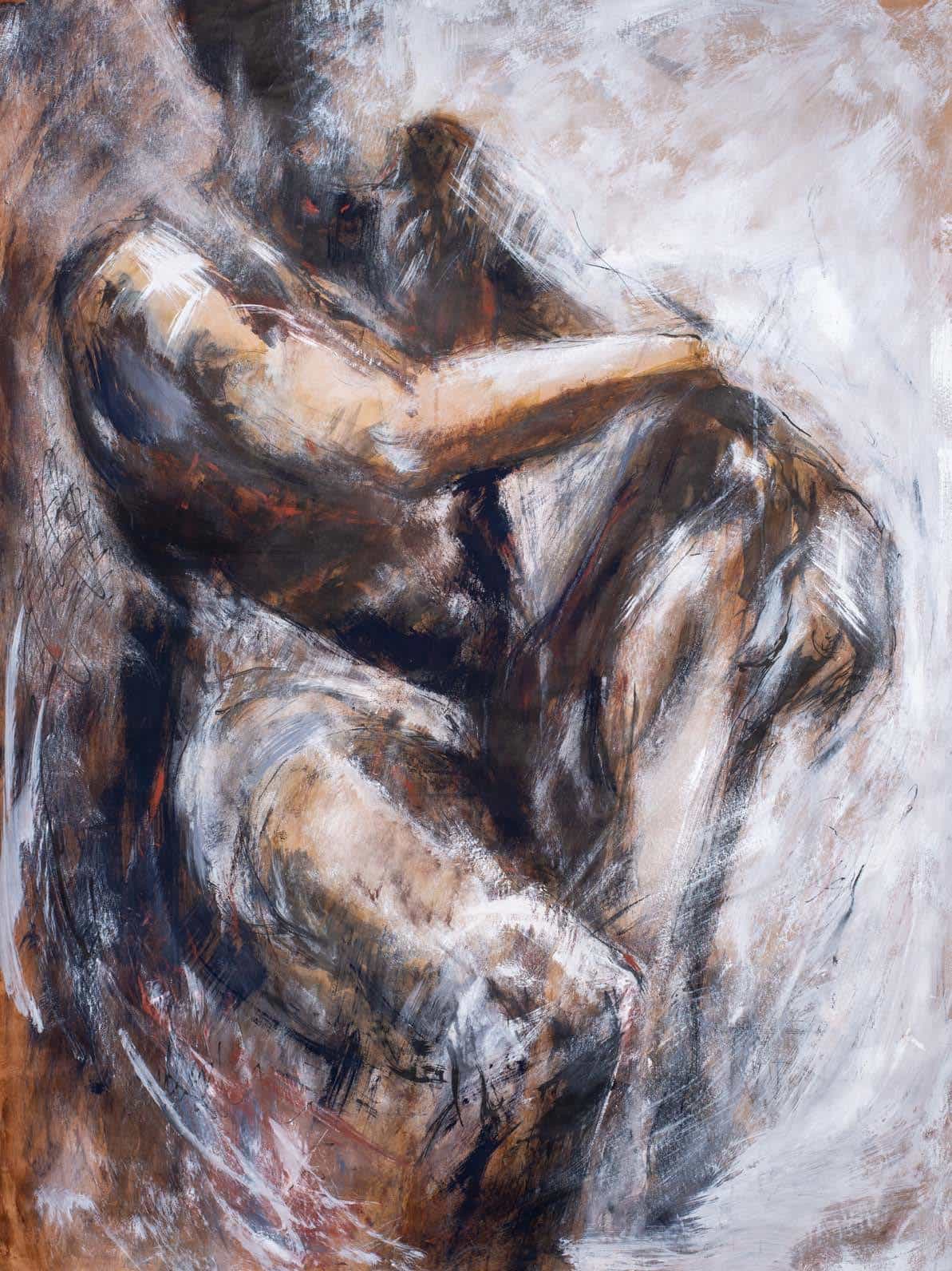

This question gained force as I contemplated his nudes in Points of Articulation: Repose, a solo exhibition presented by Yeo Workshop earlier this year. One figure, especially, drew me in. It seemed to acquire more and more heft as I stared at its striking balance of white, ochre, and black against brown paper.

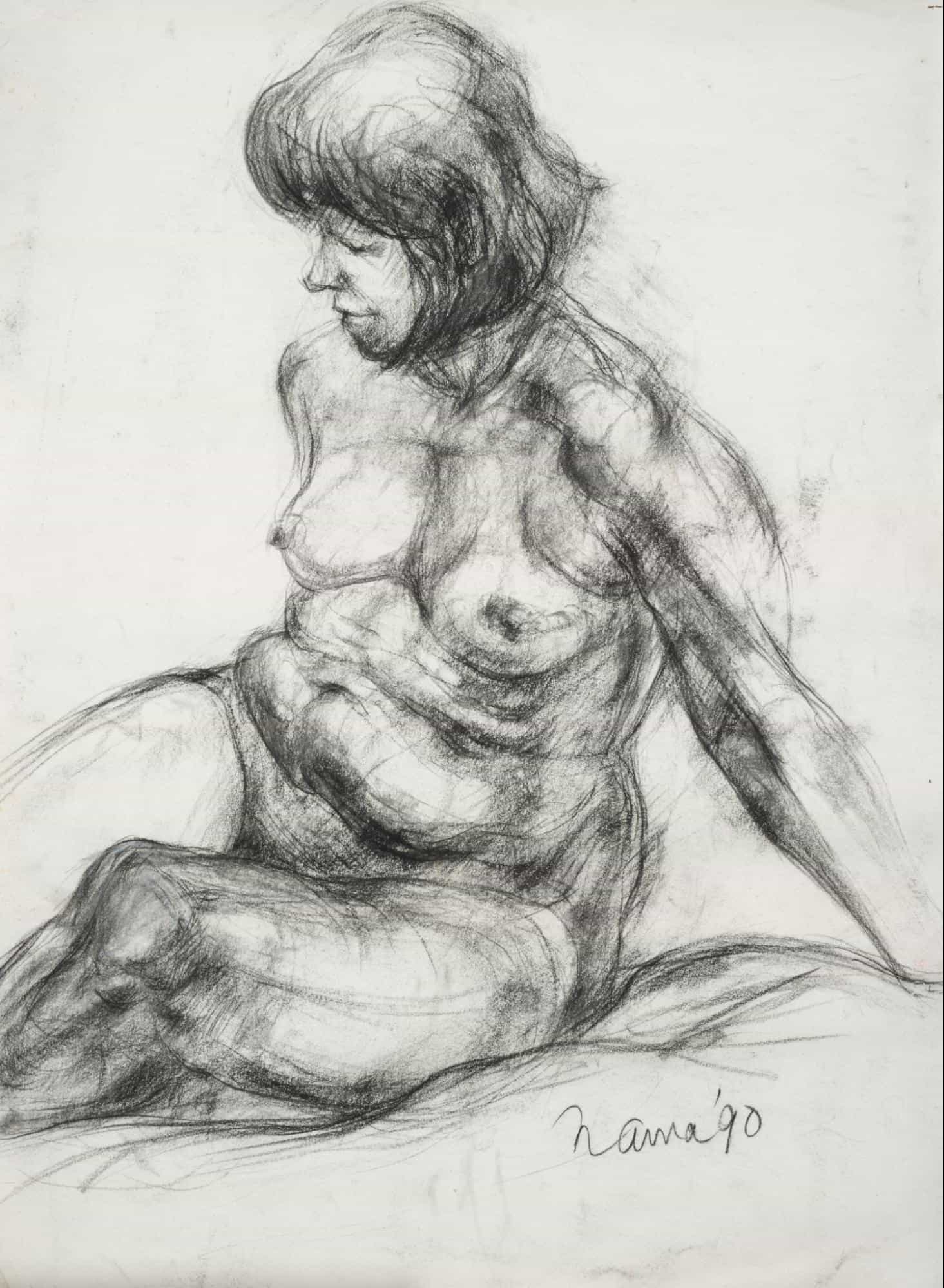

Though one’s eye is naturally drawn to look into the massed dark of the groin, Namasivayam’s nude resists salaciousness. The pose is dignified, even noble: the figure looks away and rests their arms on a raised left knee. The shapes of their arm, thigh, and belly seem solid and substantial, suggesting a real, rather than idealised, human figure. One can imagine the subject, having completed a hard day’s work, sitting down to rest with a sense of quiet satisfaction. Labour, but not laboured or over-strained.

Namasivayam’s virtuosity and masterful occlusion of detail (the face and genitalia are shadowy, obscure) invite me in for yet another look. The word “gravity” comes to mind. Something only partly articulable grounds this figure, and its weight leaves a tremendous impression.

It’s clear that Namasivayam, or Nama as he was known to friends and family, was a master of his craft. He not only practised it for a lifetime, but spent the better part of his working years in classrooms and studios teaching it, too.

Nama started out as a primary school teacher in Singapore, before receiving a scholarship to study Fine Arts at East Sydney Technical College (now Australia’s National Art School) in 1957, where he majored in figure drawing and painting. Much of his subsequent working life was then spent teaching other art teachers at the Teachers’ Training College (now the National Institute of Education). Thereafter, he held other education-adjacent posts in the Ministry of Education and taught mathematics at a vocational institute until he formally retired from teaching in 1986 at the age of 60.

Nama beyond his 60s: Pioneer, leader, and master artist

At this point, Nama might have slowed down and enjoyed his retirement, but life had other ideas. Just a year after retiring, he accepted an invitation from Brother Joseph McNally, founder of the LASALLE College of the Arts, to take on a lecturer position. There, Nama introduced a new Life Drawing specialist subject into the curriculum.

In 1990, he co-founded a group devoted to the study and interpretation of the human form with fellow artists McNally, Chia Wai Hon, and Sim Thong Khern. This informal group, which later acquired the moniker “Group 90,” would later attract prominent artists like painter Liu Kang and sculptor Ng Eng Teng, and hold exhibitions devoted to the human figure and the nude form.

Nama played a crucial role in the workings of Group 90. He emerged as one of the leaders of the group, and also undertook the task of seeking models for their drawing sessions held in LASALLE’s premises — a difficult problem in strait-laced Singapore. Nama developed a novel solution: he would approach foreigners and backpackers in the Little India area and offer them the opportunity of modelling for the artists in exchange for a fee. The group’s co-founder Sim identified Nama’s “courage and tact,” as well as his “approachable and kind nature,” as reasons for his success in this task.

Nama’s works were also distinctive for the high praise they garnered from critics. Reviewing the group’s first exhibition, Figurama, at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts Gallery in 1991, T. K. Sabapathy commented that Nama’s works were “the outstanding works in this show,” and that “his approach to the model is marked with conviction.”

Nama would go on to stage a few solo exhibitions from 1995 to 2011, though these do not seem to have been as feted as the Group 90 shows. His last solo exhibition seems to have been in 2011, at the now-defunct Della Butcher Gallery on Mackenzie Road. He died in 2013 from lung cancer and is survived by his two children.

By the time of his passing, Nama was living alone in a cramped rental flat, surrounded by his works. His health and general condition became causes for concern for acquaintances and friends such as Rehina Pereira, a media professional who got to know Nama and collect his works in his final years, and Manjeet Shergill, who was artist and manager of the Della Butcher Gallery in 2011.

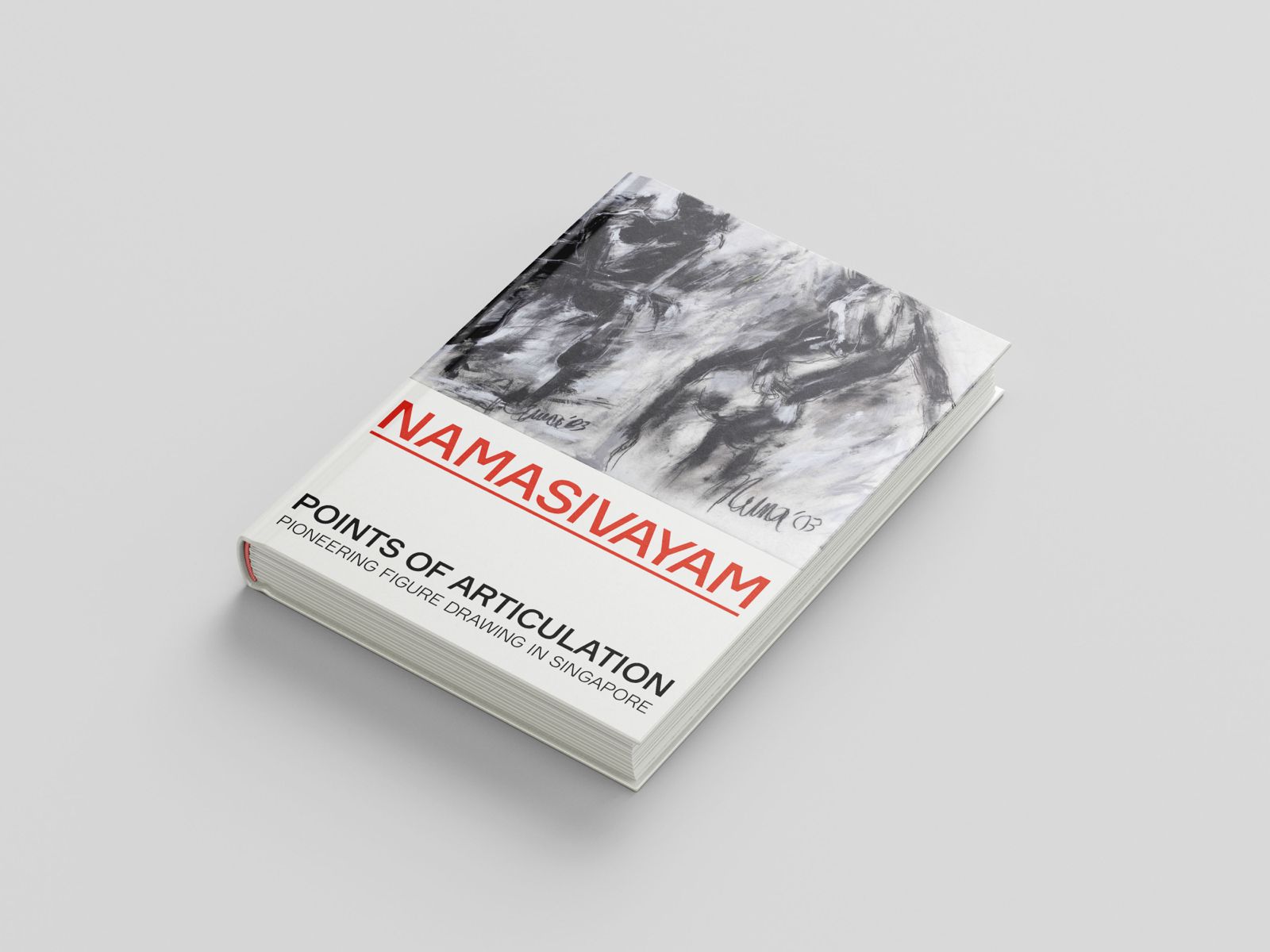

This spurred Pereira to advocate for greater recognition for the artist, leading her to approach Yeo Workshop’s founder Audrey Yeo, who embarked on a years-long journey researching Nama’s life and work. The gallery held an important retrospective in 2019 that brought Nama back to the public eye. This year, the gallery published a landmark monograph, Namasivayam: Points of Articulation, and launched it alongside a new exhibition, Points of Articulation: Repose, which ran from 5 April to 7 May.

How an artist fades into obscurity

The book posits several reasons why Nama’s reputation may have languished over the years. For one, he did not seem to have any interest in playing the game that artists must sometimes play to achieve wider recognition. In his remarks at the opening of Nama’s 2019 solo exhibition, historian Kwa Chong Guan suggested that Nama did not actively work with galleries to be represented and was not well-known in circles of curators and connoisseurs.

This is borne out by the relatively few solo exhibitions held in his lifetime. Shergill, who organised Nama’s last solo exhibition in his lifetime, recalls that Nama was at first reluctant to hold the exhibition, and was only persuaded when she couched it as more of a birthday party.

Nama also seemed to have regarded himself first as an art educator, rather than an artist, even after his retirement. Pereira recounts how when Nama met her daughter, he immediately started to teach her how to sketch and draw. When Nama visited Shergill’s studio at Chip Bee Gardens, she keenly felt his interest in her development as an artist. “I am a teacher artist. I am a teacher first”, he would say in an oral history interview in 1997.

Nama’s reputation as a respected teacher and civil servant may have sat uneasily with his love of the nude. Decades of disconnection between his pedagogy and his interests may have inhibited Nama further and made him more circumspect in asserting his identity as a master of life figure drawing, despite clear recognition by those in the know.

Dr. Victor Savage, a student of Nama’s, writes:

“… Nama kept his own artistic interests like a personal secret … his personal art was radically different from what he encouraged and taught at school. The first time I saw a public exhibition of Nama’s … I found great difficulty in relating to him as my school art teacher. There had never been a single hint of figure paintings in school lessons!”

The comparison with fellow art educator Lim Tze Peng also proves instructive here. Lim’s paintings of street scenes of old Singapore and Chinatown, as well as his calligraphy rooted in traditions of Chinese art, were more in line with Singaporean tastes at the time — and perhaps even now. By contrast, Nama’s passion to study the human form — in an era when Singapore had yet to shed conservatism around the body, even in art — made it challenging for his work to find a strong and enduring audience, no matter how well received Group 90’s exhibitions had been within a niche art circle.

A need to diversify the Singaporean art canon

To contemplate Nama’s underappreciation is also to realise how Singapore’s art-historical canon contains very few pioneering visual artists of Indian ethnicity. This becomes especially stark when compared with the attention devoted to the all-Chinese Nanyang artists and, to a markedly lesser extent, the Malay artists associated with APAD (Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya, or the Association of Artists of Various Resources).

Efforts by commercial galleries and individual advocates, though potent and commendable, may only go so far. National institutions play a critical role in revising oversimplified narratives and uncovering hidden histories, such as the pioneering contributions of Vincent Hoisington (of Sri Lankan origin) and Annaratnam Gunaratnam to Singapore sculpture.

Happily, two of Nama’s works are now displayed in the exhibition Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art, which opened in July this year at the National Gallery Singapore. Here, his works are placed in dialogue with works by other members of Group 90. Nama’s contribution in shaping Singapore’s art discourse around the human body during the 1990s has at last been given institutional recognition.

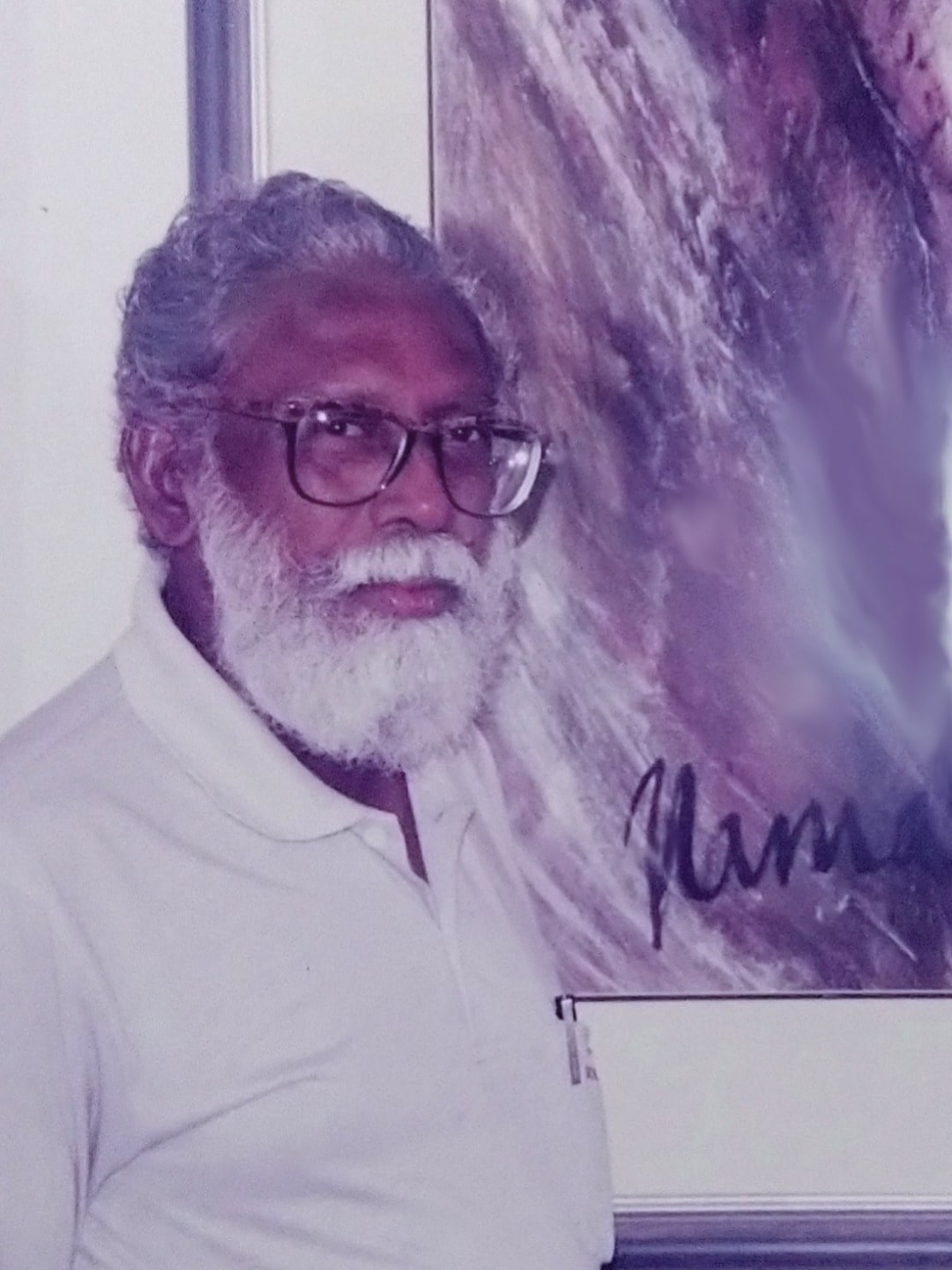

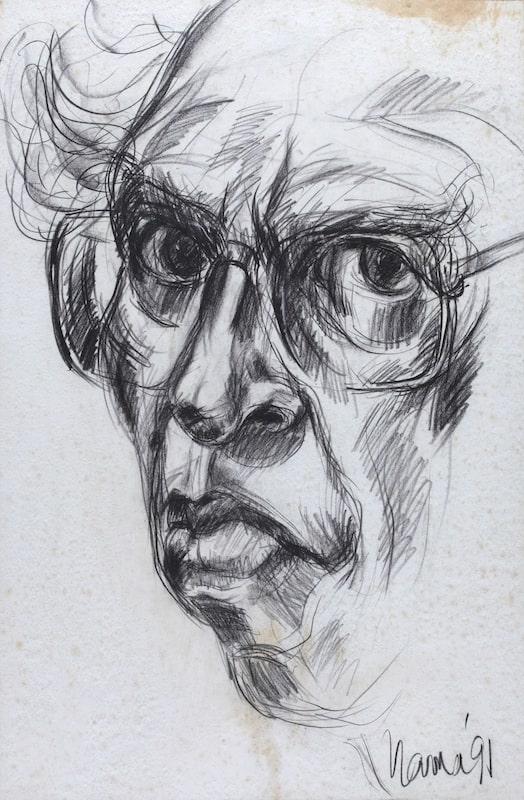

I return to the man himself, in a self-portrait sketched in 1991. There’s a sternness in his gaze, his square glasses enhancing the rigidity of his brow. His full lips are almost a pout. This man’s a tough nut to crack, I think. I also think of the effusive warmth with which his students, like Savage, recount his lessons: “Students did not feel confined to set themes and art techniques; they felt liberated.” I think of the secret passions he harboured, kept close to his heart.

Maybe we’re all ultimately a collection of contradictions, but I marvel at the contradictions that Nama lived with. Despite them, he persisted in perfecting his mastery of the nude form, drawing after drawing, a process he once described as a “never ending struggle.” It was a compulsion that did not require external validation. Even as he lay dying, Nama still clutched his sketchbook, and requested help from a nurse to execute his final works. In his own words: “My wish is to take my last breath with a drawn line.”

Bibliography

- Art of the Nude. Group 90, 1994. Exhibition catalogue.

- Chia, Wai Hon. Image Nude 1998: An Exhibition of Drawings and Paintings of the Nude by Members of Group 90 and Invited Artists. Group 90, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

- Loh, Joleen. “Recovering the Nude in 1990s Singapore.” In Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art. National Gallery Singapore, 2025. Exhibition catalogue.

- Nusense: An Exhibition of Drawings and Paintings of the Nude. Group 90, 2002. Exhibition catalogue.

- Sim, Tong Kher and Chia Wai Hon. Nuphoria 2000. Group 90, 2000. Exhibition catalogue.

___________________________________

Namasivayam: Points of Articulation is available for purchase at Yeo Workshop, The Private Museum, and Kinokuniya Singapore. Two of Nama’s works may be viewed in the long-term exhibition Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art at the National Gallery Singapore.

Header image: Installation view of Points of Articulation: Repose. Photograph by Linghui Ng.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When Art Becomes Script: T:>Works’ 24-Hour Playwriting Competition at the National Gallery Singapore

Fair Play? Rethinking Pop Culture Conventions and Their Place in the Art Landscape

What is Creative Technology? A Curator’s Thoughts on Media, Art, and Design