On 26 July 2025, the one-night exhibition Bring Your Own Beamer (BYOB): Currents drew more than 150 visitors to a River Valley shophouse. Over one night, audiences moved barefoot across three floors of projection-based pieces by 21 creatives.

Organised by Jake Tan, produced by Tusitala, and curated by yours truly, BYOB: Currents was inspired by Anne De Vries and Rafael Rozendaal’s BYOB movement, which encourages creatives around the world to stage one-night exhibitions using projectors (often called “beamers” in Europe). For BYOB: Currents, an open call brought in 16 additional participants, including industrial designers and interaction designers, alongside invited creatives like artists Kumari Nahappan, Ong Kian Peng, and Valerie Ng.

With virtually no restrictions aside from the use of projection as a medium, BYOB: Currents surfaced the obvious yet difficult question: what is creative technology? It’s a term that’s gained traction in recent years, featuring in myriad exhibitions and events, at sites ranging from the ArtScience Museum to the now-demolished Peace Centre. Through the field of media theory, and drawing examples from BYOB: Currents, let’s try to understand creative technology and contemplate its impact on how we experience art and life.

An evolving discipline

At its simplest, creative technology can be described as the meeting point of art, design, and computing. Wikipedia calls it “a broadly interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary field combining computing, design, art and the humanities.” Universities appear to be loosely in support of this definition: the Auckland University of Technology describes it as the fusion of creativity and technology to generate new solutions, while California’s ArtCenter College of Design talks about it as “the invention and hacking of technology for both artistic and practical purposes.”

Closer to home, the interest group Creative Tech SG has over 600 members on Telegram. This self-organised community of designer-artists, artist-designers, engineers, hobbyists, and misfits is a fertile environment for exploring the perceptual and experiential shifts created by today’s emerging technologies. At post-event hangouts, it’s not uncommon to see community members debating whether creative technology aligns better with art or design — an especially salient question when seeking funding from government bodies like the DesignSingapore Council or National Arts Council, which support programmes that suit their respective interests.

Taken together, such perspectives show that creative technology is not a fixed discipline but a dynamic, evolving territory, blurring the boundaries between design and new media art. Indeed, for some creative technologists, the label’s fluidity and porousness may well be part of its draw.

“Media determine our situation”

Perhaps trying to differentiate art and design is a bit of a red herring. It might be more productive to grasp creative technology, and its impact on how we experience art, through the lens of media theory. At the core of media discourse is the belief that the medium — the form in which information is transmitted — is as important as (or more important than!) the information itself.

The pioneering media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s oft-cited phrase, “the medium is the message,” speaks to this idea. However, Friedrich Kittler pushes further by saying that “media determine our situation” — implying that in any given era, technical infrastructure massively shapes our culture, knowledge, and perception of our world.

In BYOB: Currents, the core medium was projection: casting light through an image source and onto a surface. Ephemeral and fleeting, the pieces seemed to exist in a bubble, then disperse into nothingness after the event. This apparitional, numinous quality called to mind the myth of Hermes, the fleet-footed messenger of the Greek gods, who appears and disappears just as quickly.

Ong Kian Peng’s Vertical Oscillation highlighted this ethereal quality of projection-based art. As his work unfolded across the ceiling of a high vertical atrium, audiences lay beneath it, gazing upwards, as if suspended in a viscous mass below the AI-generated beings drifting above. Oriented towards the ceiling, projection destabilised gravity itself, inviting viewers into a state of weightlessness and awe.

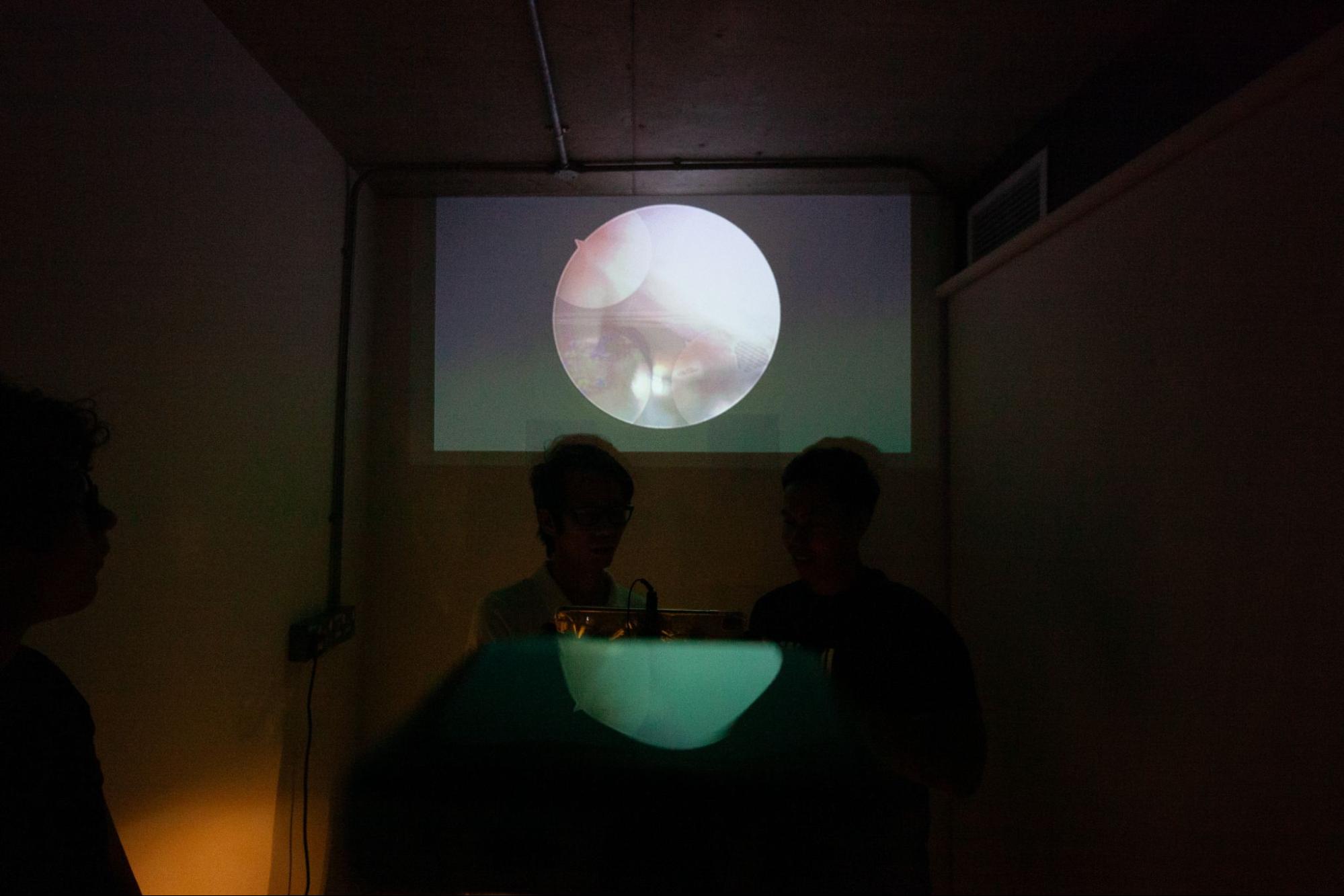

As we try to understand creative technology, it may be worth considering the etymology of media itself. In Latin, media could refer to “the middle layer of the wall of a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel.” This sense of an inner membrane, or conduit, resonates uncannily with Urich Lau’s VJ Conference: Excision, an interactive work in which the audience manipulated dials and knobs to remix the artist’s endoscopic footage from his wrist surgery. Media, here, was an infrastructure of immediacy, collapsing the distance between artist and audience and creating a visceral intimacy.

Creative technology makes our experience of art inseparable from its technical infrastructure. As audiences encounter each work through (perhaps unfamiliar) technological systems, they may also gain more immediate and intimate experiences with technology itself.

Sharing tools

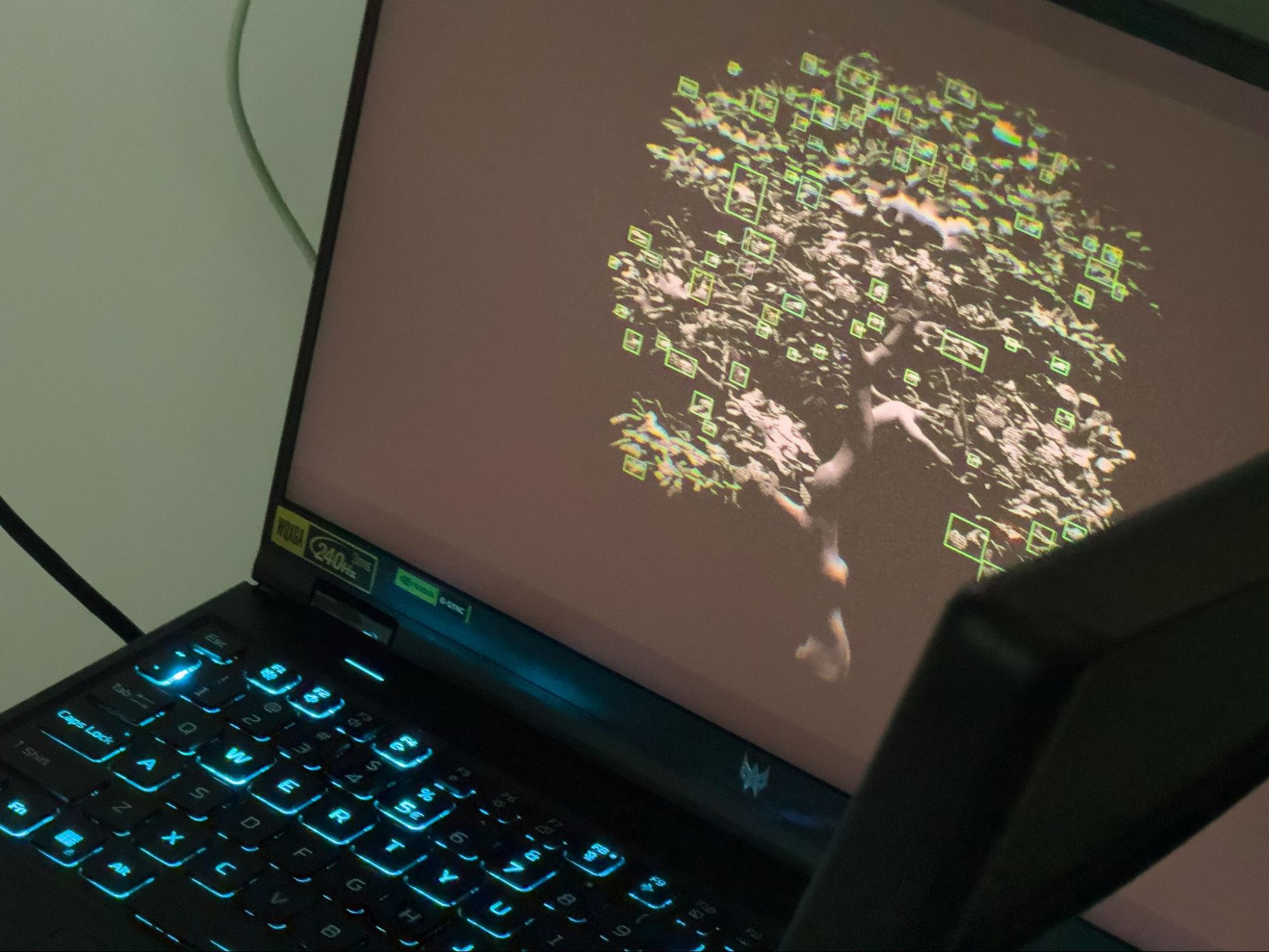

The tools used by creative technologists today make it easier than ever to create and propagate ideas among the community. TouchDesigner, for instance, is a popular visual programming tool used by artists working on projection mapping, interactive installations, and live performances. Used by several artists in BYOB: Currents, this accessible, low-code tool allows users to build projects by connecting different code components in a node-based structure.

TouchDesigner’s popularity as a tool was fuelled by collective learning, with leading creators sharing their knowledge through YouTube tutorials, workshops, and online communities. Notably, TouchDesigner also makes it extremely easy for creators to export and share custom components as .tox files (modular plugins exchanged by experts and novices alike). Like a strong tree with roots in all directions, creative technologists advance as a community, constantly creating and sharing tools with one another.

Creative technology also makes it even easier than before to bring audiences into the art-making process. Kesh’s brkpt best captures the visceral immediacy of how creative technology can short-circuit the process of turning human input into visual output. On the second floor of the shophouse, audience members could be heard screaming at the top of their lungs, competing in a gamified challenge to turn the projection screen completely white if their voices reached a certain volume. While humorous, the work demonstrated how the audience’s raw emotion could be translated into visual output within seconds.

On the other end of the temporal spectrum, Natas, nitis, nete explored this feedback loop in a tender, deliberate environment. In this interactive piece by thesupersystem and VAAS, audience members were invited to carefully lift and position branches, rocks, and leaves, embedded with electronic components, into delicate ikebana arrangements. When placed in certain ways, these configurations altered the projected visuals to showcase different trees. Through touch and technology, audience members could thus have new encounters with endangered flora native to Singapore.

When we consider the hyper-participatory experiences enabled by creative technology, it raises the question: when does audience become artist? Alongside this, AI-assisted tools such as Runway, Figma Make, and Bolt are becoming part of the same ecology. Even more than .tox files, which circulate between users as shared building blocks, AI models now act as creative collaborators — lowering barriers to entry while raising questions of authorship and consent. In this expanded landscape, creative technology forces us to ask: must the artist be human at all?

Art and life

A visitor to BYOB: Currents might have experienced the space much like a conventional gallery. Works sat on white pedestals, labels accompanied each piece, and the exhibiting areas were kept largely clear of furniture. Yet, every so often, a stray broom or pen holder betrayed the illusion, reminding us that we were in an everyday office rather than a white cube. As the show’s curator, I was interested in precisely this tension, as we grappled with the messiness of lived experience alongside the clean codes of exhibition-making.

If we get philosophical about it, perhaps this erosion of the boundaries between art and life mirrors our ongoing discourse around the place of creative technology in the landscape of media, art, and design. Creative technology not only erodes the boundaries between these fields, but also closes the gap between audience and artist. By enabling more creators than before to access and use technical tools, it enacts what philosopher Jacques Rancière has called the “distribution of the sensible”: a democratisation of who can speak, see, and act in the realm of art. Our understanding of creative technology can therefore shape our understanding of creative agency itself.

Amidst uncertainty and discomfort, it’s natural for us to want to put creative technology in a box. But that would go against the very flexibility and openness that are some of its most exciting qualities. By embracing the porousness of the field to welcome more tools and creators, we can continue to imagine high-agency paths of collective creation.

___________________________________

If you’re interested in learning more about creative technology, check out The Bring Your Own X (BYOX) Fair, which runs at Singapore Science Park till 21 September. Organised by Yeo Ker Siang, produced by Tusitala, and curated by Rachel Poonsiriwong as part of Singapore Design Week, the fair features interactive installations by creative technologists contemplating ideas of disassembly and reassembly. Visit sdw.designsingapore.org to find out more.

Header image: Work by (from left to right) thesupersystem and VAAS, LiveHumanSubject, and Akai Chew. Image courtesy of Tusitala.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

When Art Becomes Script: T:>Works’ 24-Hour Playwriting Competition at the National Gallery Singapore

Fair Play? Rethinking Pop Culture Conventions and Their Place in the Art Landscape

Solamalay Namasivayam: Singapore’s Unacknowledged Master of the Nude