What does it mean for a river as politically, spiritually, and ecologically charged as the Mekong to be translated into a white-cube museum in the American Midwest?

Mekong Voices: Transnational River Justice in Mainland Southeast Asia, on view at the Michigan State University (MSU) Broad Art Museum till February 22 this year, attempts to represent a vast river that cuts through six countries in a context more than 10,000 kilometres away. Rather than offering a tidy primer, the exhibition presents multimedia works — textile, video, installation — that speak to the river’s precarity and the communities who continue to depend on it.

The exhibition introduces American audiences to issues deeply familiar to Southeast Asia — hydropower development, cross-border extraction, militarised histories, and the everyday labour of those who live with and along the Mekong — through the perspectives of 14 artists.

Mekong Voices emerged from a proposal by the Mekong Culture WELL Project (2020–2025), an interdisciplinary initiative at MSU’s James Madison College looking into the ongoing social, cultural, and environmental issues that concern communities across the five Southeast Asian countries through which the Mekong flows, namely: Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam. (While the Mekong originates in the Tibetan Plateau in China, the study only covers the Southeast Asian countries that the river flows through.)

MSU Senior Curator Steven L. Bridges positions the exhibition as an extension of that research and a reflection of institutional desire to listen to and reflect the concerns of the river’s communities.

The cost of the human footprint on the Mekong

Phnom Penh-based artist Thang Sothea’s The Mekong Flow (2025) greets viewers as they enter the museum — and again as they leave. Made from aluminium cans and plastic bottles, the monumental sculpture reads as both a critique of the river’s mounting waste and a celebration of Cambodia’s Bon Om Touk Water Festival, when the Tonlé Sap River reverses its flow back into the Mekong.

Thai weaver group Baan Had Bai Tai Lue’s Weaving the River of Life of Tai Lue (2023) similarly tells the story of how humans bring harm to the Mekong. The lower section of the tapestry is orange-brown, representing a healthy river teeming with life and fish. As one’s gaze travels towards the top, the balanced browns become deep blues that signal a waterway empty of fish, ridden with helicopters and other vehicles of the Laotian civil war. The portrayals of Laotian bombings in Thai villages further drive home the point that the nations through which the Mekong flows are all interconnected.

Meanwhile, Thai artist-activist Ubatsat’s White Eel in the Dawn of the Exile (2019) reflects the artist’s concern for how rapid development along the Mekong is disrupting the river’s natural balance. Its dense layering of silkscreened imagery — a black boat, faint fish forms, and the stark outlines of hydroelectric dams — highlights how industrial expansion is crowding out the river’s ecosystems and the species that depend on them. Bringing these elements together at a large scale, the work points to the growing pressure that Thailand’s energy demands place on the Mekong, and echoes wider regional worries about dam construction, declining fish stocks, and the river’s changing health.

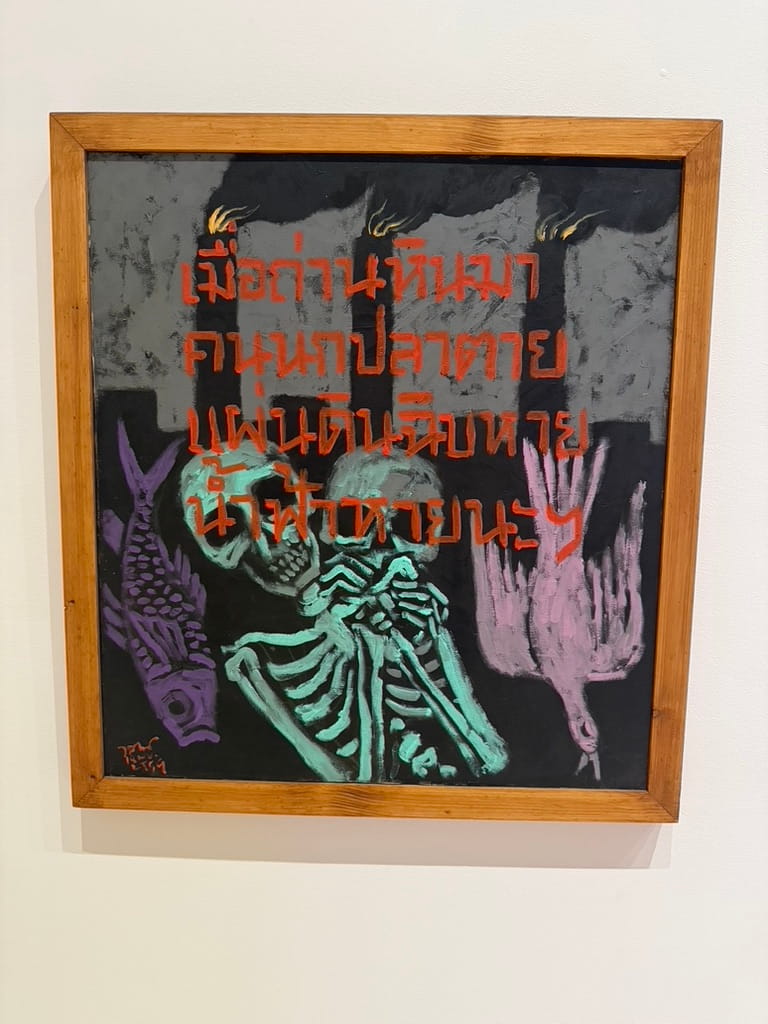

Hydroelectricity may be more environmentally friendly than non-renewable sources such as coal — which a work by Ubatsat’s compatriot Vasan Sitthiket warns against in no uncertain terms — but it too exacts a dire cost on the land. In this way, both works ask the viewer to question the wisdom of the never-ending pursuit of development.

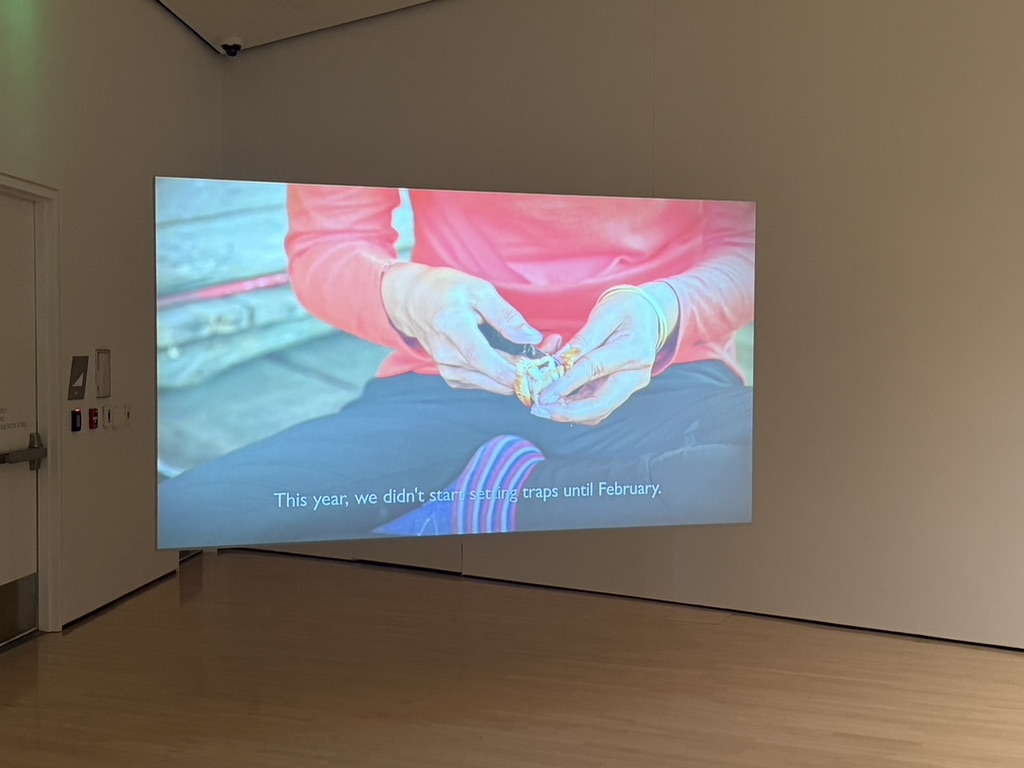

Although California-based Khmer filmmaker Kalyanee Mam’s 16-minute digital film Lost World (2018) does not directly relate to the Mekong, her work nonetheless speaks to the erasure of fragile ecosystems within the same lands. On the southern coast of Cambodia, the once-lush mangrove forests of Koh Sralau are being dredged for mud, which is imported to Singapore to serve the city-state’s expansion plans. Mam’s work is a warning against mining the land for its riches, and how that risks rootlessness and loss of identity.

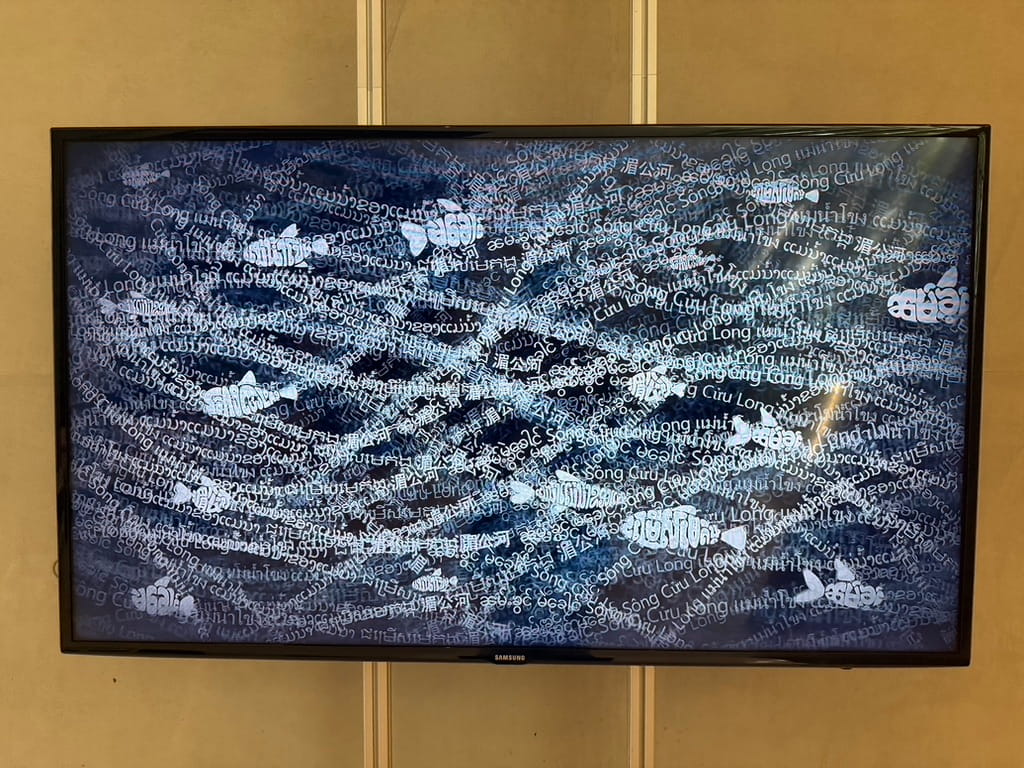

Other works in the exhibition are less clear in their intent. The video work by Cambodian artist Nim Kong entitled The River Flows (2025) attempts to relate the river’s motion with the entanglement of languages and cultures. However, compared to the critical perspectives on socio-political issues in the other works, it falls short in clarity. The lines of text that rush across the screen as mechanically-animated fish wiggling with the tide feel slightly sophomoric in their execution and expression.

Family and the fragility of home along the Mekong

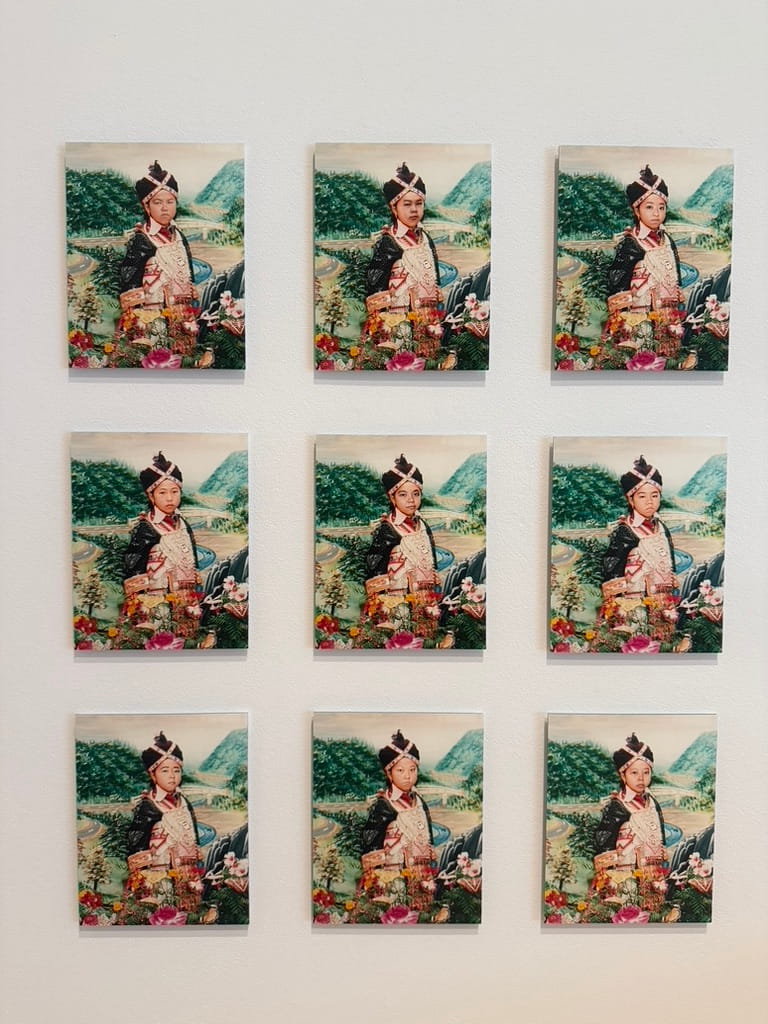

Laotian-born Hmong artist Pao Houa Her’s work cuts through the exhibition’s dominant environmental concerns with a markedly different lens. From the series My grandfather turned into a tiger, the work My grandmother’s favourite grandchild (2017) frames the Mekong as a migratory route to survival instead. The work presents photographs of Her’s cousin Pao Sao, who had been forced to stay behind in Laos during the civil war of 1962 to 1975. Meanwhile, Her and her family fled across the Mekong to seek refuge in Thailand and then migrate to the United States.

Here, the faces of Pao Sao’s own eight cousins are superimposed onto Pao Sao’s visage, such that they are defined in reference to the favourite grandchild. The Mekong plays the role of a divider of families, but also a means to a new life and safety abroad.

Works such as Cambodian photographer Lim Sokchanlina’s A boy visiting his flooded home, Stung Treng Province and Flooded village #1, Stung Treng Province (both 2024) likewise point to the fraught relationship between safety and belonging for communities that reside by a river that gives even as it takes away.

Recalling a river closer to home

Though the Mekong might seem far removed from the American public, a mere hour’s drive northeast from the museum would take one to Michigan’s own Flint River — the site of an ongoing troubled water history. There, the city’s drinking water was contaminated with lead, resulting in thousands of residents being exposed to the long-term effects of lead poisoning. This raised concerns about behavioural and physical health throughout the city when it was brought to light in 2014. Relating the Mekong to the Flint river broadens the frame of accountability, inviting the largely American audience to consider how environmental harm crosses borders, industries, and communities.

Mekong Voices makes a connection to Michigan with Native American artist Dylan A.T. Miner’s It spills // ziigibiise (2018). A three-part painting made from bitumen on felt, It spills uses material to bring awareness to Michigan’s Kalamazoo River. In 2010, the river was victim to the second-largest oil spill in the history of the United States. Bitumen, a heavy crude oil, describes the contours of the river and parallels the threat of environmental pollution across the globe.

As the only work grounded solely in the American context, It Spills serves as the vanguard for navigating the space between Michigan and Southeast Asia. There is a distinct visual difference between this gritty triptych and the other works of the exhibition. It Spills marks the end of the exhibition, a curatorial choice that allows the viewer to hear the Southeast Asian voices before returning to the American context as they exit the gallery.

MSU Broad’s Mekong Voices presents an environmentally activated call to action that brings awareness to the dire changes that need to take place across the entire globe. The works in the exhibition ground Southeast Asian voices as paramount to bringing awareness to the state of the Mekong while also bridging the investigation to the seemingly unrelated American Midwest. The exhibition serves as a much needed platform for Southeast Asian artists in the United States, and meets the goal of bringing awareness to the Mekong.

While the artworks serve as points of entry into the diverse issues around the river, the exhibition raises the question of what art and artists can do for the river. Can an exhibition of this scale incite change within the region, and what help can Americans provide regarding these issues in addition to awareness and empathy?

Some viewers may be sceptical of the exhibition’s power to make a difference in the face of these massive international dilemmas, and wonder whether the artworks can even encourage change. To answer these questions, it is important to frame Mekong Voices as a facet of MSU’s Mekong Culture WELL Project. As part of a larger institutional initiative, perhaps the exhibition will be able to help highlight Southeast Asian voices and bring attention to riverine issues in both Southeast Asia and the States, fostering solidarity across continents. The exhibition presents an accessible means for viewers to explore different cultural contexts and nuanced perspectives from the voices of the Mekong.

___________________________________

Mekong Voices: Transnational River Justice in Mainland Southeast Asia is on view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University till 22 February 2026. Visit broadmuseum.msu.edu to find out more.

Header image: A gallery view of Mekong Voices.

Support our work on Patreon

Become a memberYou might also like

Seven Ways to Spend Your Singapore Art Week 2026