The title of Ahmad Fuad Osman’s mid-career exhibition at the Balai Seni Negara (or National Art Gallery) in Kuala Lumpur, At The End of the Day Even Art Is Not Important , has taken an ironic spin and now sounds chillingly prophetic.

This comes in the wake of the Balai taking down four works from the exhibition on Feb 4, following a complaint purportedly by a Balai board member who had deemed the works “obscene and too political.” The Balai had informed the artist about its intention in a letter dated Jan 21, after initially alerting him via Whatsapp on Dec 24, 2019.

In his open letter released on Feb 10 via Facebook, Fuad claimed that the act of censorship is “arbitrary, unjustified and an abuse of institutional power,” and called for the entire exhibition to be closed immediately as it could not “remain open in its compromised state.”

“Contemporary art in Malaysia has always challenged conventions and has consistently made political commentary. Why these particular four pieces and not any of the others?”

He went further to explain that there was “plenty of challenging material throughout the exhibition.” One example of this is perhaps his 1999 work on the Malaysian Reformasi movement called Syhhh…! Dok diam-diam, jangan bantah. Mulut hang hanya boleh guna untuk cakap yaaa saja. Baghu hang boleh join depa… senang la jadi kaya! (Roughly translated, the title urges one to be quiet and not argue, as mouths should only be used for speaking and saying ‘yes’ – then only can one become one of ‘them’ and it will be easy to become rich. The use of the word ‘hang‘–meaning ‘you’–references slang from Kedah, the state which the artist hails from and which is also associated with politicians Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim and Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamed.)

The Balai’s decision came after Fuad’s exhibition had long been approved, vetted, and presented in its entirety since its opening on Oct 28, 2019. The display had initially been scheduled to end on Jan 31 this year, but the Balai had requested for it to be extended to Feb 29.

The exhibition, curated by National Gallery Singapore Senior Curator Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, has elicited positive public response and is rightly touted as one of the best exhibitions of 2019. It was an eye-opener that has arguably propelled Fuad, a founding member of the artist cooperative Matahati, towards even greater heights. Apart from printmaking, painting and performance, Fuad, who divides his time between Bali, Indonesia and Shah Alam, Selangor, has also been involved in filmmaking and theatre.

So, what are the four ‘objectionable’ works in the Balai’s so-called rogues’ gallery, and why might one anonymous board member take offense? Let’s take a look:

1. Untitled, 2012

This is a two-part work, a section of which features photographs of Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim sporting his infamous black eye, hence referencing the incident where the then–Inspector General of Police Rahim Noor had assaulted Anwar during the former’s sodomy and corruption trial in 1998.

2. Dreaming of Being A Somebody Afraid of Being A Nobody, 2019

Here, we see portraits of Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamed flanked by Economic Affairs Minister Datuk Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali and purported Prime Minister-in-waiting, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim. Read in the context of the portraits, has the political commentary underlying the title perhaps struck a sour chord amidst the ongoing power struggle within the Pakatan Harapan government?

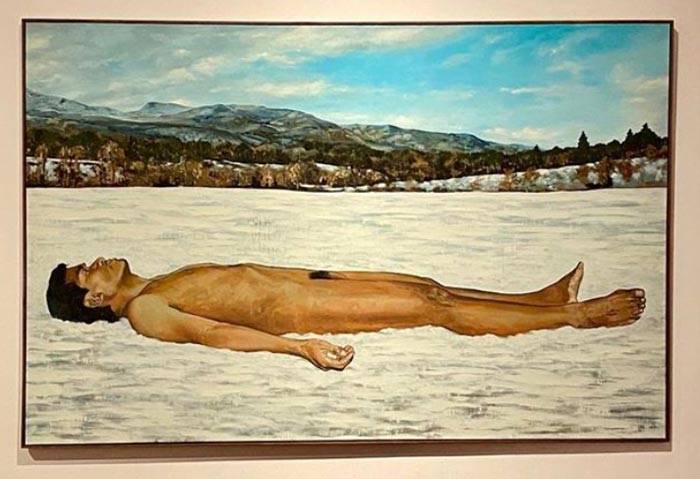

3. Imitating the Mountain, 2004

While Malaysian law may be clear that the display of genitalia in public or in the mass media is prohibited, the boundaries are less distinct when such material is considered in the context of art.

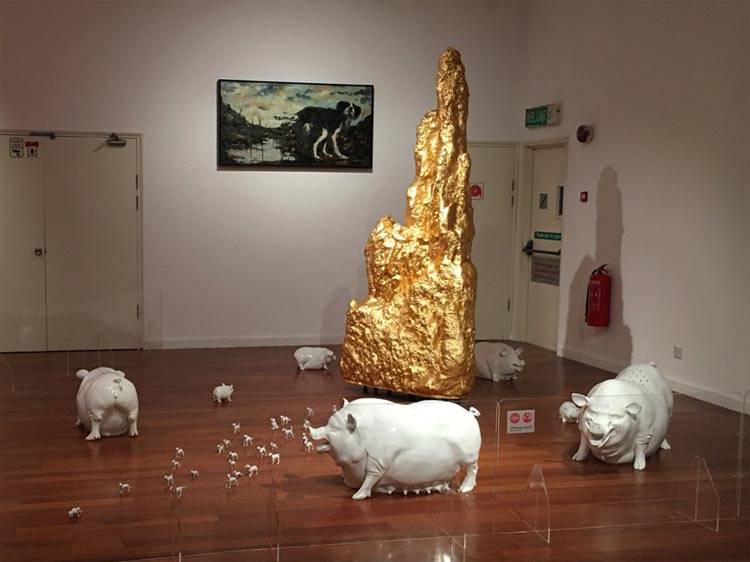

4. Mak Bapak Borek, Anak Cucu Cicit Pun Rintik, 2015-2018

According to Muslim lore, pigs are regarded to be unclean and offensive, and the mere sight of their image can cause outrage amongst the more conservative. As a result of the censorship, the fabricated pigs as seen here are no longer in the exhibition.

Up until the controversy, Fuad had been on a roll. He was selected for the Sharjah Biennial; his award-winning work, Recollections of Long Lost Memories, was borrowed from the Singapore Art Museum for a critically-acclaimed exhibition at Ilham Gallery Kuala Lumpur, The Body Politic and the Body; and he was invited to take part in the Ipoh International Art Festival.

On Feb 10, the Balai released a statement explaining that its action was part of its standard operating procedures, adding that it has the right to remove works that touch on the “dignity of any individual, religion, politics, race, culture, and nation”. However, its subsequent statement takes on an Orwellian ring: “Exhibitions are a process, and not a final product; even as the exhibition is running, this process is constantly ongoing to achieve a maturity that is suitable for our visitors and our society.”

In response, online publication Arts Equator offered this retort, “It implies that any artwork that enters Balai’s door ceases to be a ‘final product’ as deemed so by its creator. To exhibit at Balai then is to potentially relinquish power over one’s work to the ‘editing’ impulses of curators, bureaucrats, and any number of board members at any given moment.”

As Fuad pointed out, the larger issue lies with the integrity of the arts in Malaysia, and the role of public institutions in the country.

Following this incident, some 396 industry players signed a joint petition submitted to the Balai calling for greater transparency and accountability. Amongst those who vocally supported Fuad for speaking up was Zulkiflee SM Anwar Ulhaque, better known as Zunar, who himself has faced arrest, raids, travel bans and other difficulties as a result of his cartoons against the Najib Tun Razak government.

In further protest, prominent collector Pakharuddin Sulaiman, who has loaned five works to the Balai for Fuad’s exhibition, asked for his pieces to be taken down and returned.

“I don’t want them involved in an exhibition that has been compromised (by censorship),” he declared.

Another collector, Bingley Sim, followed suit.

Art censorship in Asian societies is certainly not a new phenomenon. Take for instance the censorship of Kim Eun-Sung and Kim Seo-Kyung’s Statue of a Girl of Peace at the Aichi Triennale 2019, or that of Adeela Suleman’s Killing Fields of Karachi at the Karachi Biennale, also last year.

Censorship by higher powers, such as what Fuad is facing, is not likely to go away, and Malaysia has seen more than its fair share of late (see my ‘C’ List below).

Yet, all is not lost, and perhaps this episode has a silver lining in the way that it has rallied the Malaysian art community together, and cast a spotlight on the importance of public accountability. And in all fairness, while national institutions do attempt to practice a certain modicum of freedom and fair-mindedness, the establishment of clear-cut policies on censorship is itself a complex undertaking in every society.

Joshua Lim, Director of Malaysian art gallery A+ Works of Art, notes that Fuad’s statements have set a precedent for an artist confronting the Balai on the issue of censorship.

“It takes courage,” he explained, “but it’s also not possible without support from the larger community.”

Lim reckons that the expression of strong public support by collectors Pakharuddin Sulaiman and Bingley Sim was something “unprecedented.”

“These are hopeful signs of a true ‘Malaysia Baru’ (i.e. the promise of a new and reformed Malaysia) where the people lead the way. The censorship itself, as Fuad said, was clearly arbitrary and an abuse of power. It’s great that there is, for a change, some positive resolution to this matter, because the Deputy Art and Culture Minister has now recommended that the artworks be re-installed with immediate effect. But we still have to keep pushing so that our cultural institutions fully appreciate what it means to be transparent and accountable, and so that open dialogue becomes the rule and not the exception.”

After all, didn’t Cesar Cruz say that art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable?

________________________________________

THE ‘C’ LIST

Notable events of censorship associated with the Balai

Pangrok Sulap: The Japan Foundation KL decided to remove one woodcut work by the Sabah collective Pangrok Sulap entitled Sabah Tanah Airku, from its Escape from the SEA exhibition at the APW Bangsar, purportedly due to a complaint being lodged in March 2017. The work depicted the socio-political troubles of Sabah such as flooding, illegal logging, and corruption. The collective then decided to withdraw its work from the other exhibition venue located in the Balai. Pangrok Sulap, ridiculed by the detractor as inconsequential, went on to be invited to prestigious international art events such as Sunshower: Contemporary Art From South-east Asia in Japan; the 9th Asia-Pacific Triennial in Brisbane, Australia; and the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in India.

1st KL Biennale: Malaysian art collective Pusat Sekitar Seni and Indonesia’s Population Project withdrew from the 1st KL Biennale at the Balai in 2017, because they claimed that their work, Under Construction, was removed and that they were barred access to it.

The Subtitle: Suddin (Samsuddin) Lappo’s barbed painting The Subtitle made a statement against bodek (fawning) culture. It was removed from a group exhibition in 2017 with a notice stating that it was “Temporarily removed for maintenance,” but it was later returned to the wall. It depicts a subordinate kissing the hand of the Godfather Marlon Brando, with a caption below that reads, “Aku akan bagi mereka dedak yang takkan (bisa) ditolak” (roughly translated as ‘I will make them an offer they couldn’t refuse’). Art Asia Pacific suggests that the translation was construed as political commentary on then- former Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamed’s attacks on opponents.

Bakat Muda Sezaman Competition Finals: In 2014, the Balai took down artworks by competition finalists Cheng Yen Pheng and Izat Arif Saiful Bahri on the basis that they caused distress amongst gallery visitors, despite the works having already been on display for several months. They were removed in advance of a visit by Minister of Culture and Tourism Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz. Cheng had spray-painted the words, ‘ABU,’ on her painting, referring to the term ‘Anything but UMNO’, a popular political slogan. (‘Abu‘ also means ‘ashes’ in the Malay language.) Izat’s installation featured a rack of t-shirts bearing Arabic letters “Fa” and “Qof,” a play on a common English vulgarity.

Friends In Need: In 1986, Nirmala Dutt Shanmughalingam’s work, Friends In Need, which critiqued US military action in Libya, was removed before the opening of the show Side by Side: Contemporary British and Malaysian Art, at the Balai. The work was later reinstated in the exhibition and is now in the collection of the National Gallery Singapore.

___________________________________________

Editor’s Note: Update as at Sunday, 16 February 2020. Following mounting pressure from artists, collectors, politicians and the public, Balai Seni Negara has restored all 4 works it previously removed from Ahmad Fuad Osman’s exhibition. The Balai’s chief director, Amerruddin Ahmad, said that the gallery had taken public feedback into consideration in making its decision.