At the start of any hiking trail stands a map for the eager traveller.

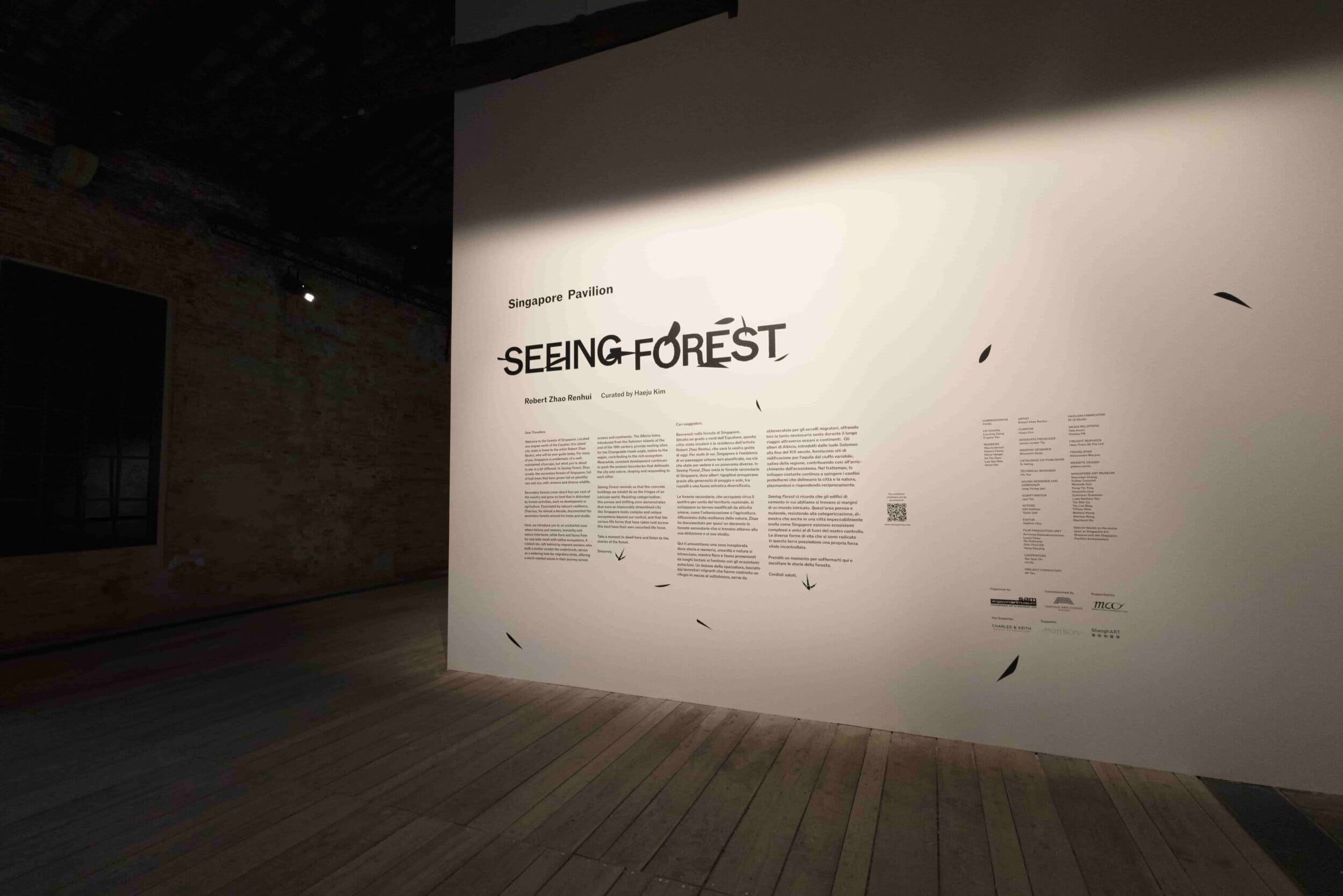

Robert Zhao Renhui’s Venice Biennale presentation Seeing Forest, curated by Haeju Kim, is contained within the second floor of the Sale d’Armi in the Arsenale, a cluster of four 16th-century barracks built with brick and stone. As we enter, we are presented with A Guide To A Secondary Forest of Singapore, an imaginary forest map introducing his extensive research at “Queen’s Own Hill”—an old name for the Gillman Barracks compound—and his own home. A giant albizia tree, common in Singapore’s secondary forest, anchors the map. Its roots grasp a shattered brick housing, with branches extending towards more trees, carrying myths, encounters, histories, animals, and visitors local and invasive. We make a mental note of things to see, take a photograph of Zhao’s map just in case, check our equipment, and roll down our sleeves.

I think we are ready. We start our hike. We enter the forest.

“Secondary forests are second chances for nature to find a way to reclaim its place after environmental and human disruptions,” states Robert in the Biennale press release. This is a story of reclamation, resilience, invasion, and hope, where plants and animals build homes in secondary forests naturally regenerated from the decay and destruction—whether man-made or organic—of primary forests populated by native tree species. Within it, we find an abandoned dustbin becoming a waterhole, a shattered concrete drain becoming a river.

Life persists and thrives in forgotten trash.

“The symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum.”

Philip K. Dick, “Valis”

The first site we visit on our hike is Trash Stratum, an installation echoing a crumbling cabinet of curiosities, made from stacked wooden boxes and objects Zhao collected on his walks in the forest. If one looks carefully, one can spot a samsu (DIY illicit liquor) vessel from the 1950s, fragments of medicinal bottles issued to the Japanese Imperial Army in the 1940s, and ceramics from England and Scotland in the 1920s-1950s hidden in the wooden box frames. Interspersed with the trash are 12 screens showing video footage of hidden cameras Zhao placed in the forest, capturing wild-life such as the collared kingfisher, crab-eating macaque, cobra, and buffy fish owl. These are not specimens laid out for our inspection within a scientist’s glass cabinet but encounters only apparent if you look carefully enough.

The trick is to remain quiet, be patient, and keep your eyes open.

A loud bang causes us to turn around.

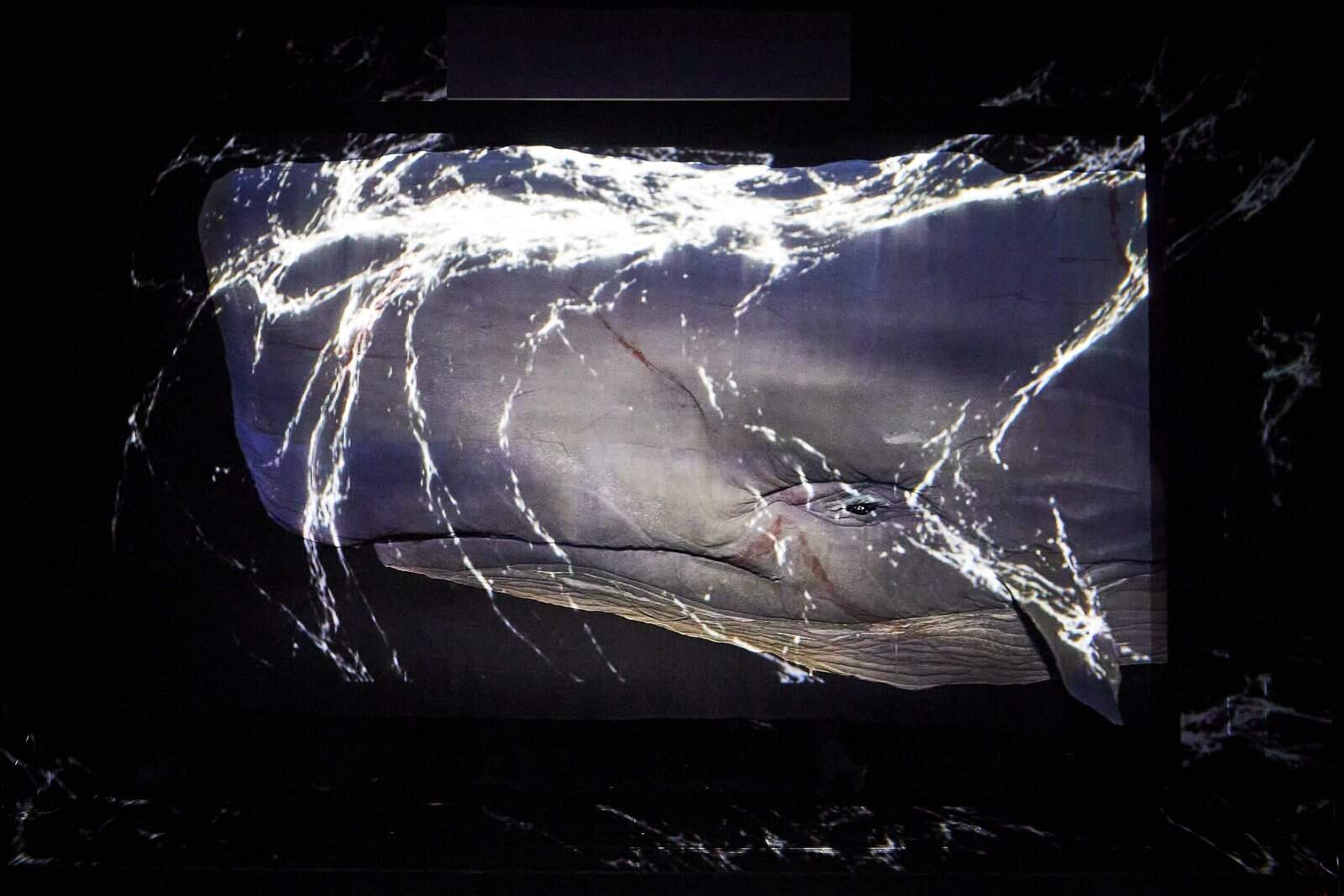

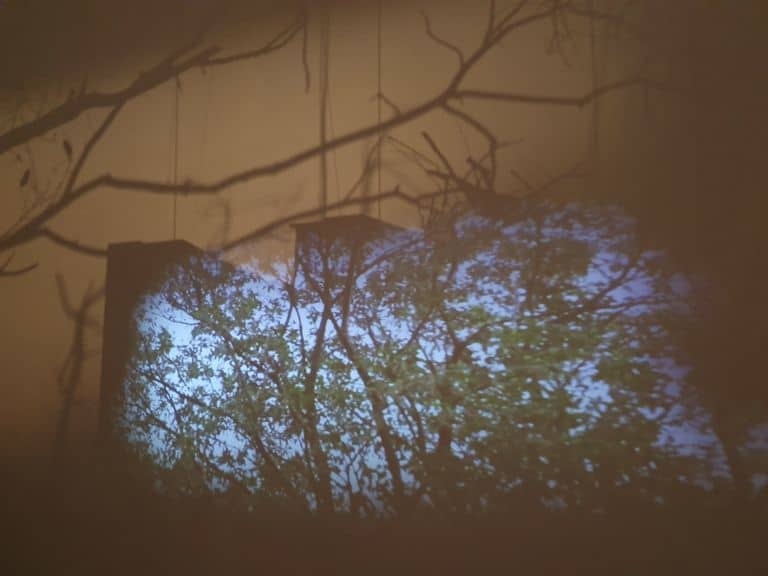

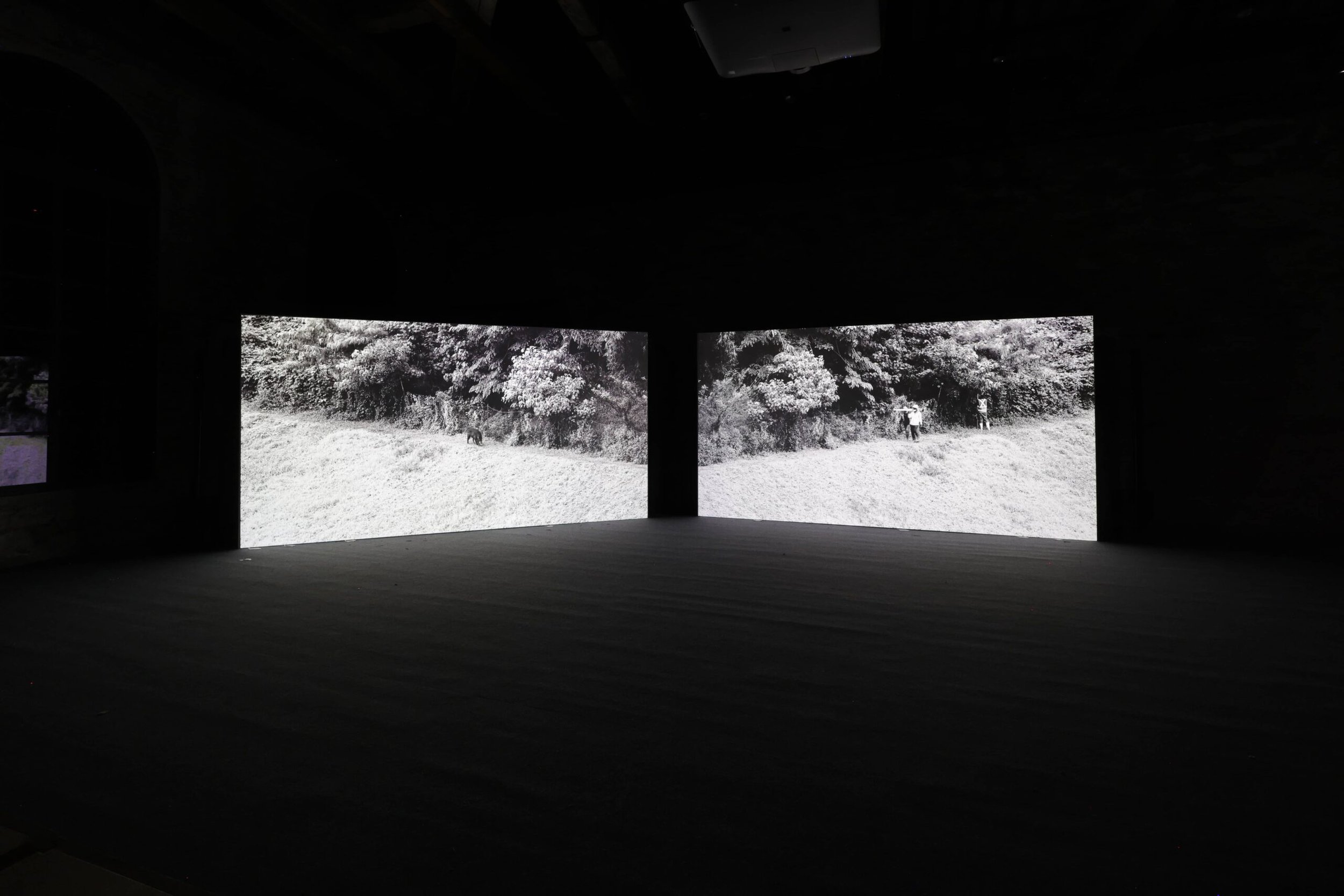

Two large video screens enwrap us. The Owl, The Travellers and The Cement Drain is a two-channel video featuring footage collected with zoom lens photography, motion capture and body temperature cameras installed within the forests. We spot a sambar deer, which was thought to have disappeared in Singapore. How rare! Oh wait, a monitor lizard! A wild boar and its piglets scurry into the tall grass. Close by, construction workers are clearing forests for land development. Next, we hear a familiar cacophony of long tailed parakeets rustling in the trees at 7pm, perhaps in protest. A parakeet stares right back at us. Tadpoles hatch and wriggle in a pool of collected water. Two travellers converse about ghosts while one takes a piss.

As we walk on further, a buffy fish owl looks out the windows of the Sale d’Armi, its back turned away from us. Buffy (2024), a mixed media installation, is poised on the far end of the pavilion. Does it miss home? Is it watching the Venetian Lagoon, hunting for prey? Is it taking a pit stop as it crosses the Adriatic Sea? Is it wondering why it was brought all the way here to contemplate on a crumbling throne of wood and debris erected in a city eaten away by salt, bacteria, and over-tourism?

As a fellow Singaporean, I find myself grieving the loss of our natural habitats, ecosystems, and primary forests in our small city. Our city consumes right to its edges. Zhao’s work reminds us that nature is resilient. It takes over and makes use of what we discard, it invades and flourishes despite urbanisation, and wilderness seeps out from within even us. Life is unruly. Zhao’s practice is a tribute to resilience, predicated on patient observation and a deep respect for our environment.

In Zhao’s forest, we are the foreigner, the traveller inspecting the homes of wildlife flourishing in the wake of our interruptions. We are their neighbours, seeing through Zhao’s eyes. The presence of Buffy reminds us that we, including Zhao, are also tourists in Venice. Foreigners. How do we respect and care for the land which hosts us, these works, and our movements?

The main title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia is Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere. It comes from neon sculptures by the Paris-born, Palermo-based collective Claire Fontaine, which reference the name of a collective that fought racism and xenophobia in early 2000s Italy. The exhibition’s curator Adriano Pedrosa states that the phrase has (at least) a dual meaning: “First of all, that wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter foreigners—they/we are everywhere. Secondly, that no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.”

As we exit Zhao’s forest, we return to the body of the Biennale, a transitional space between pavilions. Nearby sits Quiet Ground by South African artist MADEYOULOOK, who thinks of land as method, epistemology, educator, repository, and archive, contemplating the history of forced migration in Africa. A sonic-scape of traditional songs, combined with what appears to be wheat or grass suspended from the ceiling, brings us to a different kind of communal forest with a dry, grassy smell. The work reminds us of home, conversation, community, and harvest.

Roberto Huarcaya’s Cosmic Traces at the Peruvian Pavilion, meanwhile, imprints light, dust, water, plants, and insects onto a trailing 30 metre photogram made in the heart of the Amazon, its photosensitive material activated by lightning. With a wood sculpture by Antonio Pareja and piano composition by Mariano Zuzunaga, the sonic-visual-object environment creates a tomb-like enclosure, a deep darkness, paralleling the Amazon as a natural darkroom with the sky as a photographer. Another forest, this time at night.

So many forests.

These pavilions, and so many more, act as neighbouring ecosystems situated side by side, housing forests sprouted on what were former shipyards and armouries in the Arsenale. From guns to grass, from boats to watering holes, from artillery fires to lightning flashes. These transformations happen as the Venice Biennale returns once again—invading, presenting, inhabiting for 100 days before it is pruned once more.

What I draw from my hike across these confounding, contemplative, and deeply reflective works is a thought: that perhaps what is needed in these most challenging times, is to let the soft, moist, messy wilderness take over. For us to remain still for a little while longer, to give time for grass to grow and wildlife to thrive between our broken hearts, our toes, our trash, and our violence. In this stillness, we can watch with awe the life that gushes in.

___________________________________

Seeing Forest, the Pavilion of Singapore at the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, is on view in Venice until 24 November 2024. The exhibition will be reimagined and presented in Singapore in January 2025 at the Tanjong Pagar Distripark. Visit the Singapore Art Museum website for more information.

Header image: Installation view of A Guide to a Secondary Forest of Singapore (2024), as part of Seeing Forest at the Singapore Pavilion at Biennale Arte 2024.