The Hevea brasiliensis, also known as the Para rubber tree is native to Brazil and is sometimes referred to as the ‘weeping tree.’ Cutting the tree bark results in white sap – that contains latex – leaking out. But in Marvin Tang’s latest exhibition Of Weeping Trees, the act of cutting holds a deeper meaning – it represents the tears and pain shed by rubber plantation labourers in Singapore’s early years.

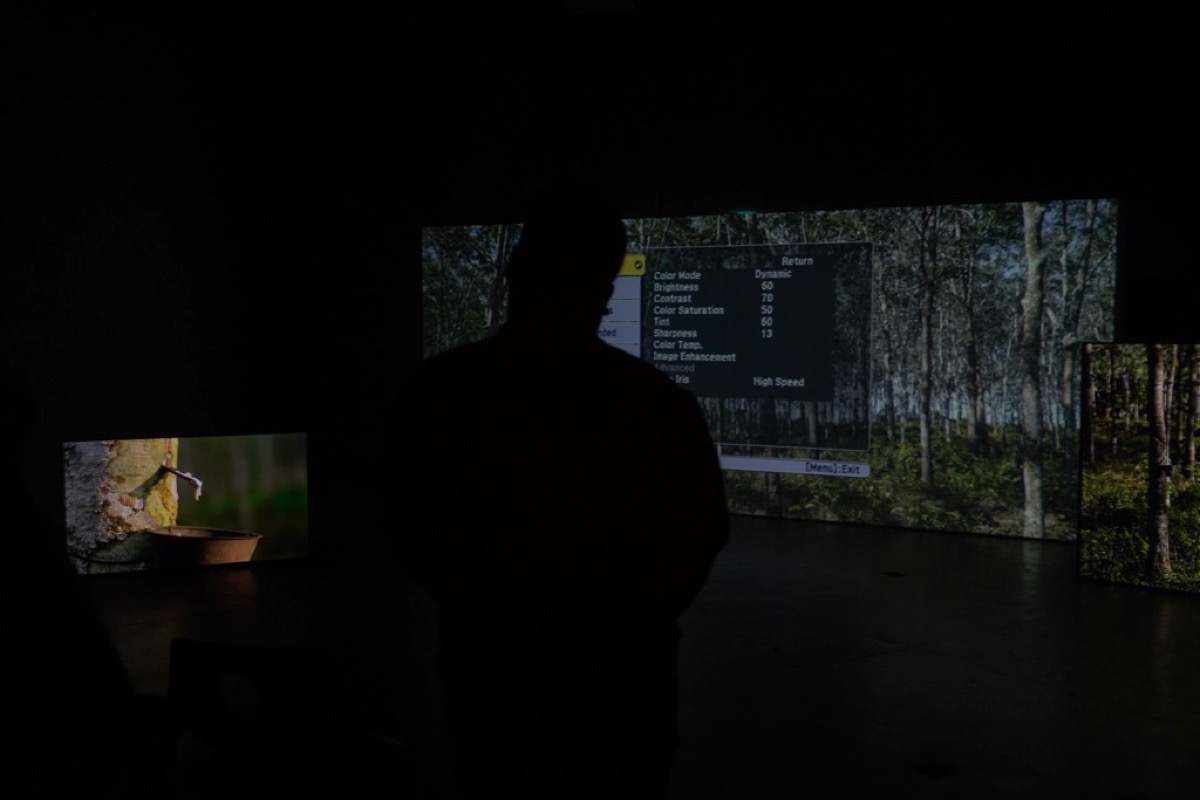

Held at Objectifs’ Chapel Gallery, the 23-minute long video installation has been described as one of Tang’s most emotional works yet.

As viewers step into the darkened room, they are brought on a meditative and evocative journey through history. In this atmospheric space, I feel momentarily lulled into a hypnotic trance as the narrative unfolds before me.

Amidst the serene slow-tracking shots of forests, Tang’s narrative brims with undercurrents of tension, punctuated by a sense of quietly veiled anger expressed by the labourers towards their colonial masters. Viewers are made to wrestle with the complex themes of colonial imperialism, the cost of progress, power dynamics, oppression, collective pain and trauma.

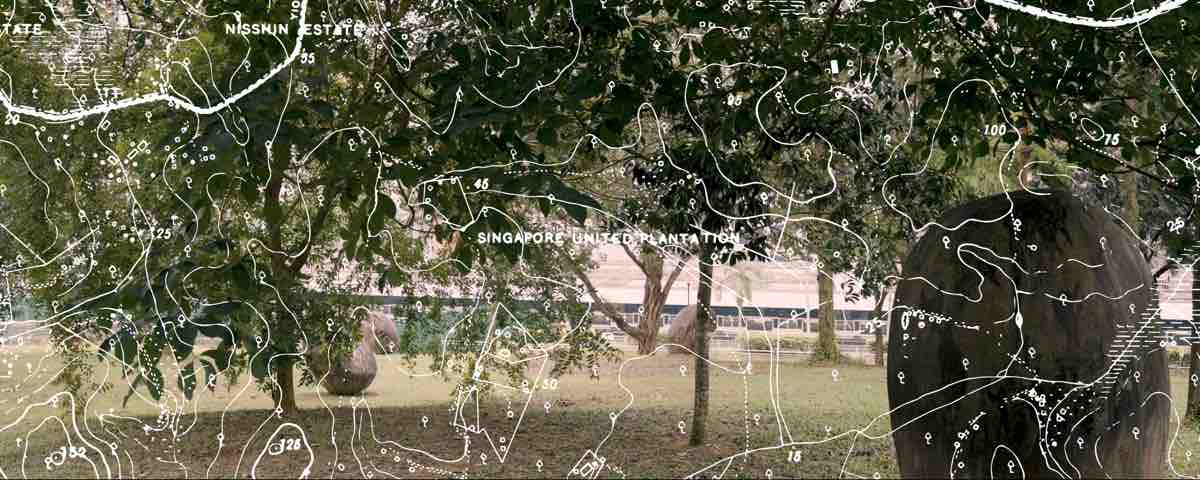

Over a series of chapters, the exhibition examines the parallel narratives of Para rubber trees, and the plantation labourers who arrived in Singapore in the 1900s to work on them. Through foregrounding the contents of colonial postcards, contemporary surveys of former and existing rubber plantations, and the haunting songs sung by these labourers, the exhibition teases out the connections forged over the contested ground of history, economy and ecology.

We sat down with artist Marvin Tang to find out more about the genesis of his project.

How did you get interested in this topic?

It started all the way back in 2017, when I was doing my Masters in Photography at the University of Arts London. I got interested in exploring the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, which housed many species of plants from all over the world, and its relationship with the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

While the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is very beautiful, it also made me think about global plant migration and the plantation economy in the colonial era, when the British established its overseas colonies between the late 16th to 20th centuries. The British Empire, at its height, was the world’s largest, with conquests spanning North America, Australia and Africa. With their botanic gardens, the world became a planetary garden, and Kew was the headquarters where valuable plants and seeds found during expeditions to far-flung corners of the world gathered. One of the key reasons for expeditions was to seek out new plants that could reap economic benefits for the British Empire, with rubber being one [such plant]. As more rubber plantations expanded across Malaya, there was a need to bring in labour to support these plantations. As such, large numbers of indentured labourers from India and China came to the region in hopes of seeking better lives through working on plantations.

That led to massive labour migrations, with British officials and Chinese and Indian labourers flocking to Singapore for work and opportunity. Singapore’s ‘Garden City’ story doesn’t just begin with founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, but dates back to our colonial history. In my previous residency with the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore [in 2020], I focused on the history and evolution of the Wardian case, a glass container for growing and transporting flora devised by British physician Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in 1833. It was a device that I first encountered in the Kew archives, where 22 seedlings were moved to Singapore with these cases.

In the late 1890s, the botanist at Kew regarded Singapore to be a good habitat to cultivate rubber due to its similarities in the environmental habitat with the region of Pará in Brazil, where the Hevea brasiliensis comes from. Thus, I embarked on a long-term research project called The Colony, which investigates the movements of seeds, plants and people via the botanic gardens. Of Weeping Trees is the conclusion to the first chapter of The Colony.

What was your artistic and research process like?

I enjoyed going through books, research papers and archival documents to gain a deeper understanding of the context [of British Imperialism] and forming my own perspectives. Many letters and books about rubber, which were written by British officials and can be found in the Kew Library and Archive, focus on the economic benefits or ways to adapt the material. However, the story of how the British collected the rubber seeds and the experiences of the plantation labourers were not often mentioned. And even if they were, they almost seemed like footnotes. For this latest work, it got me thinking that I could look beyond the movement of seeds and plants in geographical terms, and into the human aspect of it. The narration [in the video] is largely derived from written sources. Chapter one stems from books written by British explorer Henry Wickham and a journal by Wickham’s wife. Chapter two borrows text from translated folk songs from Chinese and Indian plantation labourers.

What did studying the folk songs teach you about the labourers of the time?

I was looking at the work of researchers Kingston Pal Thamburaj and Logeswary Arumugum. Both have written a number of papers looking at Tamil folk songs. In one of the papers, Logeswary Arumugum examined these songs to draw an impression of the experience of the plantation labourers.

She had very neatly categorised the issues the plantation workers were facing — the sense of regret when they were shipped to Singapore, the trials of their journey, the hardship faced and fatigue while working on the plantation, and more disturbingly, allusions to sexual assault by the colonial masters.

For instance, these are some of the lyrics in the folk songs:

I came in an old ship to rubber tap

Given 45 cents and a broken backbone

Given 35 cents and a broken joint

From dawn to dusk

Toiling like cows

Clearing the land

We often assume plantation workers to be disempowered, voiceless and silent, but through the songs, you know they’re not silent. They had a voice. And that voice became one of the key voices I wanted to explore in this work.

Why the decision to present the work in a video format?

There is a large source of imagery of Malaya available today both on the internet and in physical archives. I have also personally collected postcards of colonial Singapore since 2017. As such, presenting the work as a video installation allowed me to scale the presentation and confront viewers with a narrative about rubber that they might not have encountered previously.

Tell me about the other visual motifs that crop up in the film?

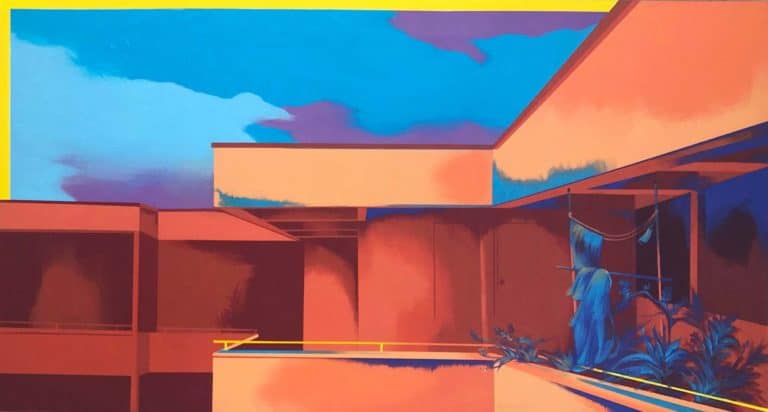

There are moments where you see an apparition moving about in the plantation. As much of this video highlights the notion of the unseen, I felt it was important to visualise the non-human aspect of the narrative. [Here, it’s] a form, that represents the forlorn stories, the trees and the memories that it carries. The film also depicts overlaying graphics of maps over the green parcels of land and new developments in Singapore. It’s a reference to how things are constantly changing in Singapore, how buildings now take the place of former rubber plantations. There’s a sense of erasure and amnesia as our land transforms so quickly with time.

Once in a while, you can still stumble on patches of rubber trees in the environment, which come as a reminder of our past. For example there’s a small patch in Kent Ridge Park and at Woodlands too.

What’s the meaning behind the exhibition title?

Hevea brasiliensis is the rubber tree, nicknamed ‘the weeping tree’, ‘the tears tree’, or the ‘caoutchouc’. Latex is extracted from the ‘bleeding’ of this tree. In my research, I also discovered a song which describes how the labourer would weep [out of helplessness] under the weeping tree. It felt quite fitting and I thought it was important to show the duality of the term.

What do you hope will be the key takeaway for audiences?

The whole narrative of the rubber industry tends to focus on economic and monetary aspects — the success story, so to speak. I hope audiences would consider the power dynamics behind these massive plantations and remember the people who have toiled and suffered in the making of this narrative. Some of the scenes were filmed in Malaysia, and I was confronted with scenes of plantation after plantation. These issues of marginalised voices don’t just relate to Singapore, but to Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam today. The rubber narrative extends to Thailand and Vietnam where plantations still exist to feed the needs of natural latex.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Of Weeping Trees runs at Chapel Gallery, Objectifs – Centre for Photography & Film till 10 September 2023. Click here to find out more.

Click here to learn more about the artist.