Most followers of Indonesian art will be familiar with Affandi, who is arguably one of the most recognizable names in the field; a rockstar granddaddy if you will, of the Indonesian Modern. We couldn’t therefore have made a trip to Jogja without looking in on the Affandi Museum. Not having done too much research into the space before our visit, we weren’t quite sure what to expect. Imagine then our surprise when we stumbled upon this:

If you’ve visited Studio Ghibli in Tokyo, you’ll have some sense of what the Affandi Museum is like. In a nutshell, the whole thing is modelled on all his favourite stuff :- from the banana leaf-inspired rooftops, to the numerous paintings and sculptures of his most-loved animals and people, to the horse-drawn cart that he modified for use as a living area for him and his wife.

But before we get into the museum visit proper, here’s a little about Affandi himself.

He was born in 1907 and was particularly well known for being a founding member of the Pelukis Rakyat (“People’s Painters”), a revolutionary artist group founded in 1947; which stood for the depiction of the genuine realities of Indonesian life, warts and all. Pelukis Rakyat felt strongly that art should be relevant to and understandable by, the common man on the street. This response was in many ways a backlash against the art forms advocated by Indonesia’s Dutch colonial masters, who much preferred looking at idyllic landscapes and lush tropical imagery (i.e. the mooi indie style, look at the section on “visual arts”) , to the grim realities faced by their colonial subjects. See here for an example:

Exhibit A: A landscape work by Abdullah Suriosobroto (with thanks to Wikipedia)

Exhibit B: A Captured Spy (1947), by Affandi

No prizes for guessing which work reflected Dutch colonial impressions, and which one spoke to the authentic experiences of the Indonesian people.

So how did Affandi fit into all of this? He was a key player in Indonesian realism, and his works – although beautifully rendered- often reflected the unvarnished and ugly complexities of life. A Captured Spy, for example, depicts a man caught for spying during the Indonesian war of independence and who provided information of a guerrilla attack to the Dutch military, in order to save his family from starvation. Affandi’s empathy for the traitorous spy is evident, in his sympathetic and nuanced depiction of the spy’s downcast, sorrowful eyes and bloodied features. Meanwhile, the bold, dark brushstrokes of the soldier looming overhead, add tension to the piece.

Affandi was also famous for not using traditional implements in his painting, such as paintbrushes; and would often just squeeze paints directly from their tubes onto his canvases. We watched a video of this at the museum, and it was absolutely fascinating (see it here).

What really struck us at the museum though, was how Affandi’s life seemed to be so full of love; and rich with keenly –felt experiences of life. A warm, fuzzy feeling just infuses the whole space and you can’t help but leave feeling happy and inspired. He adored his first wife Maryati, and his oldest daughter Kartika, and the museum is absolutely stuffed to the brim with works of them.

Affandi later married again, but apparently at Maryati’s insistence because she had been unable to provide him with a male heir (we were told to set aside our feminist rage at this point, because, well, cultural and generational differences). Still, he and Maryati are buried side by side at the museum, and from looking at his works, you would never have realized that he’d married again.

If you do visit the Affandi Museum, don’t go expecting MoMA or Met standards – this isn’t that kind of place and you’ll just be setting yourself up for disappointment. That doesn’t mean that the museum is inefficient or badly run, it just operates in a different way. There are no official curator tours, or guiding schedules, or docents, or audio guides.

What it does have, are warm, enthusiastic guides who will randomly approach you (if you don’t go looking for them first); and who will be happy to give you a spontaneous tour if you’d like one – just don’t forget to tip, if you’re happy with the service.

A word of caution though, not many speak English. While you don’t need academic-level knowledge of Bahasa Indonesia, serviceable Malay will go a long way in understanding nuances of the tour which you might otherwise miss. Notwithstanding, the wall texts are very decent, so don’t fret too much over the language issues.

Here’s some of the other cool stuff we came across, if you’d like to see:

This, we were told, is Affandi’s “life symbol”, made up of hands (important for painting), feet (important for moving forward) and the sun (important for life and everything else). It rather romantically appears in works that the artist thought were technically good, or which marked an important part of his life and artistic practice. (Our guide seemed to allude to the life symbol appearing more frequently on works once Affandi realized the economic value of the symbolism, but we prefer the first explanation!).

Affandi also loved his chickens, subscribing to Islamic folklore that they could see angels -crowing in the morning for example, was symbolic of angel-sighting. Accordingly, the museum features many depictions of this noble bird.

He also had a thing for boy’s toys. Here’s his specially-designed Mitsubishi Gallant which was modified to look like a fish, another of his favourite animal friends. Legend has it that the car company wanted to duplicate the design for mass production, but he refused to let them.

Here’s his pool, which looks so much like Gaudi’s work don’t you think?

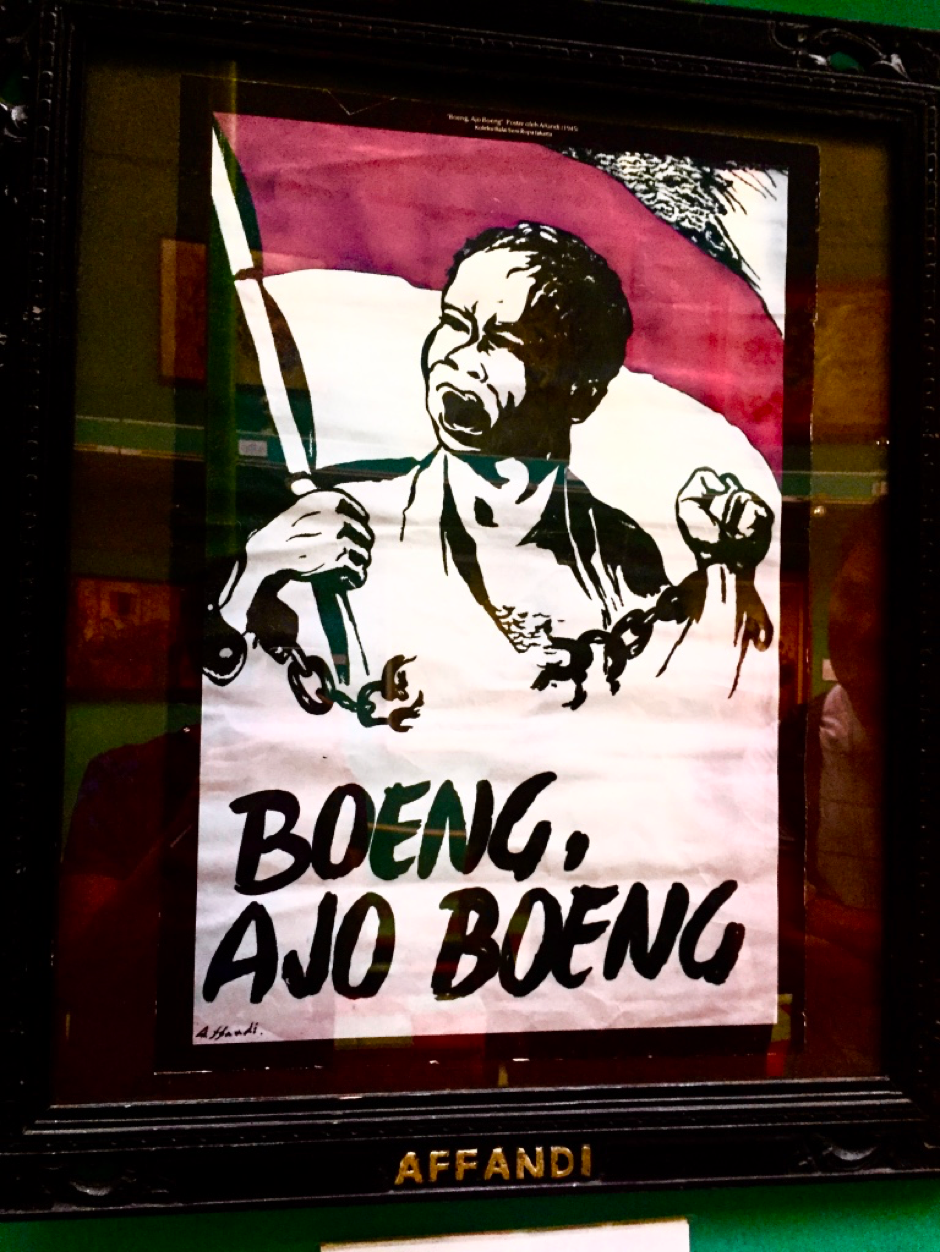

And in case you (like me) are always on the lookout for cool merchandise, you can buy t- shirts with awesome “Boeng Ajo Boeng” prints from the museum shop. The slogan means “Come on, guys!” and refers to calls that Indonesian hookers would make to entice patronage amongst passing men. Affandi borrowed the slogan for a series of political posters commissioned by Sukarno to awaken the Indonesian fighting spirit during the Indonesian revolution . (Just a word of warning, Indonesian sizes tend to run on the small side, so size up, if you’re making a purchase for someone who isn’t there to try it on).

All in all, this was a really special place; infused with all the passion and fervor of artistic genius and a life well-lived, to its very fullest. We had such a lovely time here, and would highly recommend a visit.

The Affandi Museum: – Jl. Laksda Adisucipto 167 Yogyakarta 55281; Email: affandimuseum@yahoo.com, museumaffandi@gmail.com

PS: If you aren’t planning a trip to Jogja anytime soon, you can also view Affandi’s work at Singapore’s National Gallery