Why do collectors collect, and how do they shape their collections? If this is something that you’ve ever wondered about, then stopping by Material Agendas, the 2020 edition of the IMPART Collectors’ Show might prove worthwhile.

Centring the exhibition around the theme Material Agendas, curatorial advisor Tan Boon Hui has chosen 19 works of art from 12 private collections around the world that highlight the adventurousness of both artists as well as their collectors, in the way that they “go beyond conventional definitions of what art can be made of”.

Vice President of the Global Arts & Cultural Programmes and Director of the Asian Art Society in New York and former Singapore Art Museum director, Tan shares that he has noted a rising appreciation for the use of unconventional materials and approaches in art amongst the global collector’s market in recent years. One should thus not be surprised to find materials as diverse as sequins, hair and even bindis in this show.

Thai artist Jakkai Siributr’s Hi-So, for instance, glitters from the plethora of sequins that have been meticulously hand-stitched onto the canvas. The words “hello and goodbye” are emblazoned in emerald green against a predominantly violet background, while the embroidered figures of go-go boys and minor celebrities gaze back at the viewer from their perch on their personal lotus thrones. The artist uses his extensive knowledge of textiles to synthesise iconography from various aspects of Thai culture for his commentary on the socio-political realities of living in modern Thailand.

The collector of this work, Thai-based Tom Van Blarcom, shares that his approach towards collecting is one that looks out for “a special beauty… that uniqueness, whatever it might be”. Curiously captivating in form and colour, Jakkai’s idiosyncratic reflections upon contemporary Thai issues certainly fit the bill.

For Filipino collector couple Lourdes and Michaelangelo Samson, they collect because “someone once told (them) that the secret to a good marriage is to find a joint passion”. Upon this advice, they have built a collection of art that they hope reflects not just the diversity of artistic practices in Southeast Asia, but also their personal journey together as a couple.

The Samsons have loaned Manila-based artist Mariano Ching’s Heads from their collection for the occasion of this show. Comprising alternating spliced segments of the busts of Christ and the Virgin Mary, this work utilises found objects that are ubiquitous in predominantly Roman Catholic Philippines. The artist has decorated the sides of each cross-section with intricate pyrography markings that invoke the cosmos, such that peering into each gap provides insights into a wholly different reality.

The way that Ching used “found objects in a surprising way to engage with religion, which is still so much a part of daily life in the Philippines” drew the Samsons’ interest in his work. It is a prime example of what Tan means when he declares, “The art of the present has freed itself from the limitations of material expectations. The basis of art making is now more than ink, paint, carved stone or casted metal and some of the most interesting contemporary work sees the artist testing the limits of material possibilities”.

Elsewhere, young Singaporean artist Odelia Tang’s Time is a Weight I Carry tests material limits through scale, as she mounts an inhumanly large installation of synthetic hair. The artist shares how she relates to this uncommon medium in a very personal way, in that it charts her fragile relationship with the passage of time, and how she grows and matures through the way that she cares for her hair.

Tan sees Tang’s approach to the material as an “attempt… to speak a global language of challenging and moving away from pure conceptualism. This reflects a turn away from the turn, if you will: where the last generation focused on the dematerialisation of the object and ideas, recent artists have returned to the material and primacy of the object”.

Collector couple Richard Nijkerk and Lauren Nijkerk Bogen, to whom Tang’s work belongs, comment, “We like to collect work that is difficult to categorize – is it a painting, a poem or a sculpture? Or is it a bit of it all? We like the usage of everyday items.” And it is indeed from the mundaneness of hair that Tang has woven meaning, thereby creating art from the everyday.

While for some, the impulse to collect may be born from a sense of curiosity regarding the artist’s alchemical process over their chosen materials, beauty remains a powerful driving force for others. Indian collector Sunil Hirani notes, “The art I am drawn to… has to evoke a reaction – but it must be beautiful and elegantly executed.”

The work that he has contributed to this exhibition is Indian artist Alwar Balasubramaniam’s Gravity. Here, a fibreglass cast of the artist’s likeness emerges droopily through a white wall, such that it seems as though the head hangs so heavily as to pull down the plane of reality. As much about the unseen as it is about the seen, Gravity is a prime example of what Balasubramaniam (commonly referred to as Bala) likes to call “casting the invisible”. In its minimal simplicity, it possesses a universality that gives it a timeless appeal.

At the same time, Tan comments that Bala’s work is a mark of confidence from an Asian artist who avoids orientalising his own work in order to capture a market. Though the artist used to receive comments that his work was ‘not Indian enough’ in its lack of overt signifiers of Indian culture, he continued to focus on his preoccupation with metaphysics, and eventually found success without pandering to the market.

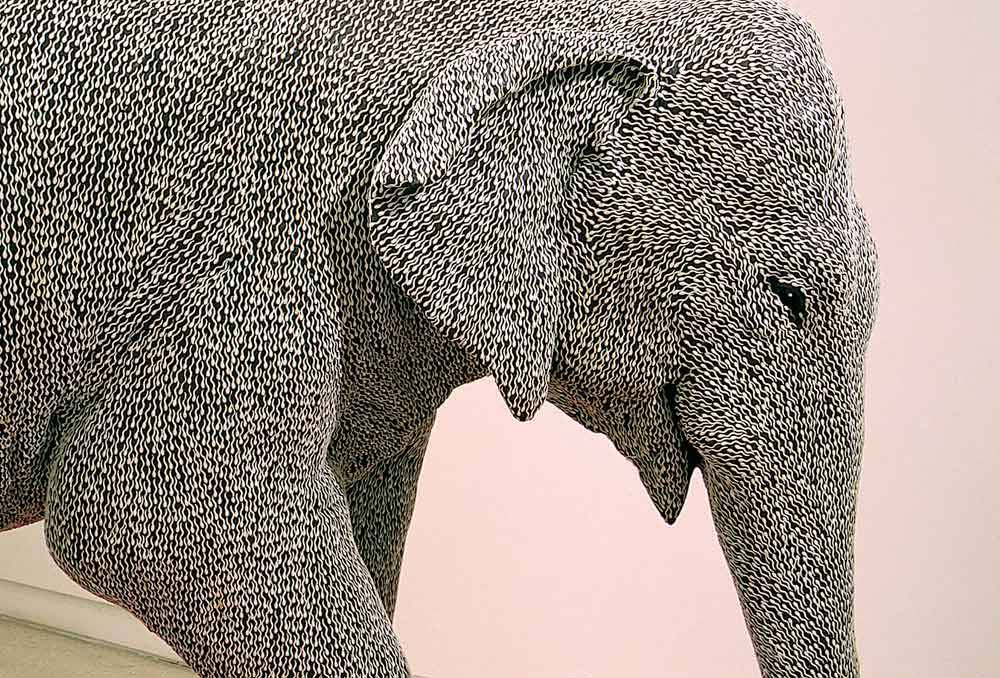

It is a far cry from the (literal) elephant in the room, then – Indian superstar artist Bharti Kherr’s I’ve Seen An Elephant Fly features a life-size baby elephant covered with serpentine vinyl bindis from inch to inch. These bindis read more as visual pattern than religious symbol in the way that the artist has decontextualised from their original functions. And if something so iconic can be so easily defamiliarised, then what lays beneath when we strip away the easy visual markers of India’s exoticised identity? Would what we understand about India then still be as recognisable as a baby elephant?

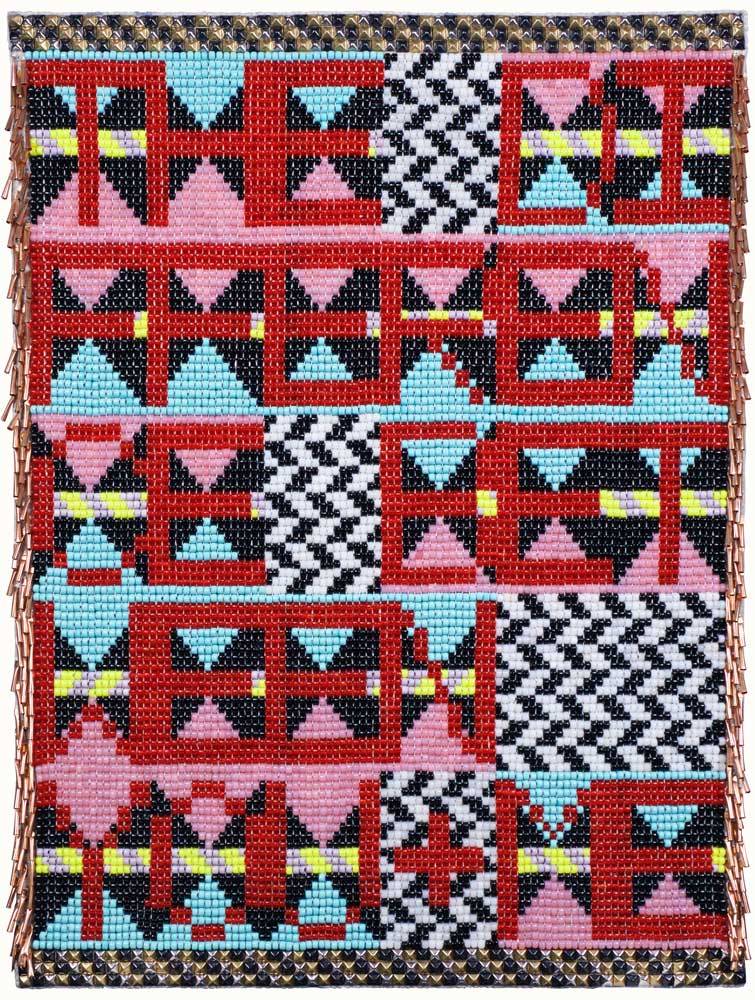

But it is never easy to navigate issues of identity as an artist. Choctaw-Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson knows this well, and it shows in the way that his work masterfully resists being pigeonholed. As Kealey Boyd writes, “You can understand the history of the bead trade or intertribal powwow music but it won’t get you far with Gibson because he is operating in an open structure that denies a predetermined reading. His amalgamation of materials, compositions, and influences betray the narrow profile of a “native artist.””

The Difference Between You + Me is but one such example. This elaborately embroidered tapestry of glass beads pulls together elements from sources as various as indigenous art and craft, music, politics and art history, and spits out a uniqueness that could almost only result from the specificity of the artist’s personal biography. I am not surprised when Tan notes that there has been a recent surge in collectors’ interest in traditional crafts such as textiles, weaving and dyeing, if artists like Gibson and Jakkai have been using these traditional mediums to interface the history of their people with the complex realities of living in these contemporary times.

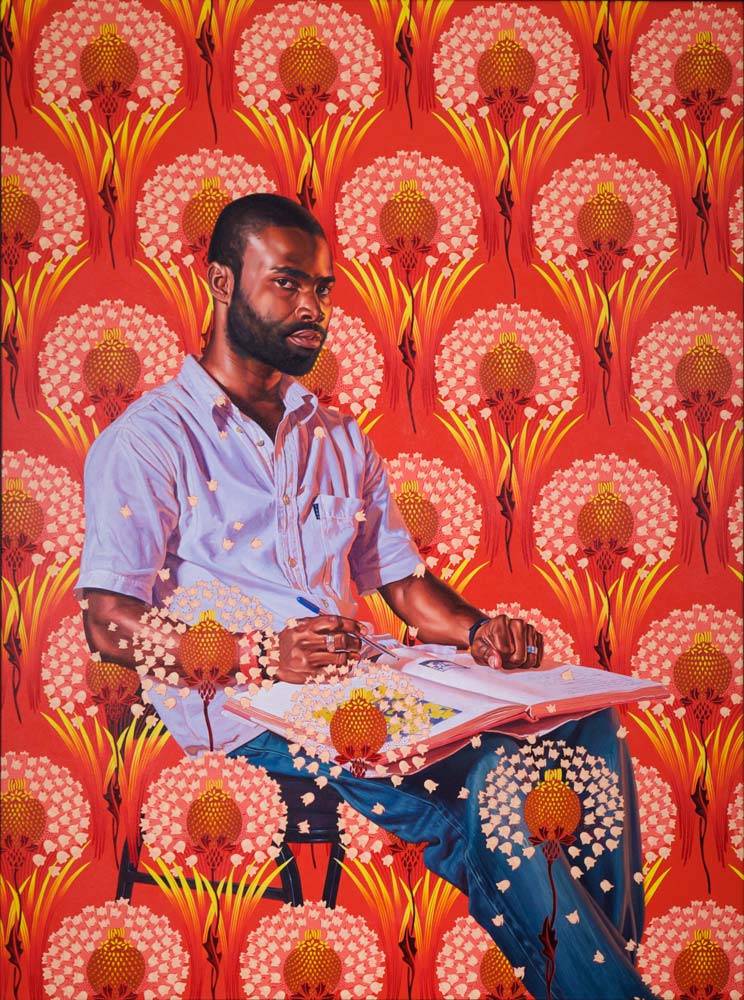

Finally, in an exhibition that prides itself on showing works that test the limits of material possibilities, it might surprise you to find more than a couple of oil paintings. But one might yet count on this age-old medium for a few more tricks, as Nigerian-American artist Kehinde Wiley subverts the white-dominated tradition of portraiture to cede power to the disenfranchised black male body.

Wiley retains the opulence of the ornate patterns from bygone eras, and even the grandeur of the titles, but substitutes the usual historically important white men in the paintings with anonymous black men that he casts from suburban streets. Through such appropriation of art historical tropes, he uses “the power of images to remedy the historical invisibility of black men and women,” as Eugene Tsai, curator of the Brooklyn Museum puts it.

And so oil paintings continues to stay relevant in spite of artists’ ever expanding forays beyond the traditional modes of portraiture that once dominated the field of art. If the motive of Material Agendas is to explore how all material and their attendant histories – no matter how old school or everyday – are fair game in the hands of an artist, then this agenda has certainly been fulfilled.

Now, who says painting is dead?

________________________________________________________________

The IMPART Collectors’ Show 2020: Material Agendas is on view at the School of the Arts Singapore (SOTA) Art Gallery from 10 to 19 January 2020.

This article is produced in paid partnership with Art Outreach Singapore. Thank you for supporting the institutions that support Plural.

Feature image: El Anatsui, Coins on Grandmother’s Cloth, 1992 (detail), on view at Material Agendas.