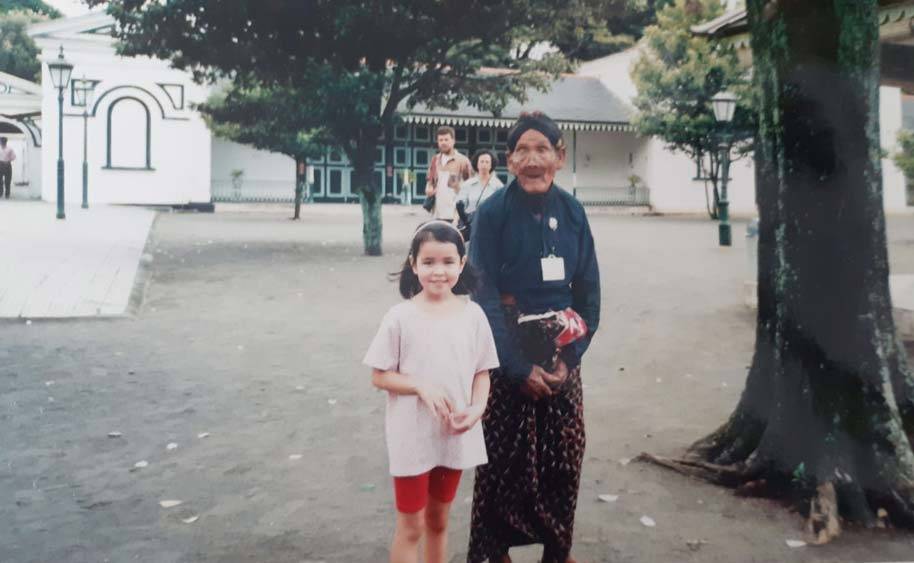

I have a vague memory from when I lived in Yogyakarta as a six-year-old child:

I am in a leotard, jumping around in a ballet class in an extraordinary house filled with paintings. There is a river gushing behind the house. I remember that the teacher was a beautiful Indonesian lady full of energy. Someone said that her father (or was it her mother?) was a famous Indonesian artist, a maestro.

It is a hazy memory. But fast forward 24 years, and I am telling my mother that I will be interviewing Kartika Affandi, a famous Indonesian painter, for an upcoming exhibition. “You used to do ballet at her museum!” My mother exclaims. Could it be? Was she my ballet teacher before she became a painter? As I do my pre-interview research, I find images of the museum, and recognise it immediately. Impossible, I think to myself, she is 85 now, 24 years ago she would not have been a ballet teacher. Her father, Affandi, was a self-taught Indonesian painter renowned for his expressionist paintings. Did I really take ballet lessons at the Affandi Museum?

I dare myself to find out during the interview.

Kartika Affandi, at the age of 85, has the vivacity and dynamism of a 20-year old. She exudes wisdom, love and an infectious optimism. Kartika has lived a life rich in experience, both good and bad, and tells her stories with such animated clarity. As an artist, she has painted across the three main political eras of Indonesia; Soekarno, who supported artists, Soeharto, who cracked down on activist art, and the post-Soeharto era, which saw Indonesia propel to where it is today.

Kartika is keenly aware of her position as a female artist, and recognises that being female has not been easy for her as an artist. “People will always compare you to men. I can do everything, just like a man. But if I was born again, I would still want to be a woman.”

Kartika’s artistic process is incredibly unique. Her technique – finger painting directly from the paint tube – was taught to her at the age of seven by her father, who had taught himself this, along with composition and colour combination. Kartika, like her father, does not paint in a studio but rather prefers to paint outside in her surroundings. Her visit to Singapore is primarily motivated by the opportunity for her to capture the Chinese New Year festivities of the city with live painting – possibly the first time in recent memory that a maestro has ever done this in Singapore. She draws inspiration from observing the faces, animals and nature around her, and enjoys the interaction. She feels at home amidst a spectating crowd, and even jokes about being given coins by onlookers when painting in public.

“They don’t know about the price of my painting!” She exclaims, laughing.

While Kartika is very much her father’s daughter, she has struggled with finding her own identity. In the past, critics had observed that she was walking in the shadow of her father. This bothered her.

“I don’t want to become Affandi number two,” she declared to her father.

In support of her mission to find herself, her father gave her some money. Kartika went to Paris, where she visited the Louvre and was mesmerised by old Japanese and Chinese paintings that were done in black and white. She could not understand why the lack of colour inspired her so much, especially given her father’s lively paintings. Kartika also visited Malaysia and Thailand, painting what she saw, including opium farmers in Chiang Rai. She then decided to combine her awe of the traditional paintings with her father’s painting technique, to create her own artistic language. Finding her own way was a journey that also involved practicing yoga, studying painting restoration in Vienna, and converting to Buddhism (primarily due to her disagreement with her late first husband’s polygamy).

She shows her re-emergence as a painter in her work Rebirth, and sees this piece as an important marker in her journey.

“This is how I start to be myself about life,” she tells me.

Kartika’s visual language is very much influenced by her surroundings and her values, which family and love lay at the heart of. Flowers feature heavily in her paintings. She poignantly explains that flowers are exchanged in love, in happiness, and in mourning when sending off the departed. “For me, flower is everything. Even I try to look as a flower too,” she points at a flower neatly pinned into her hair.

Flowers are as much her trademark as her positive demeanour is. One of the key pieces of the exhibition If Walls Could Speak is a painting titled Lotus, which comprises of three interchangeable panels. It is vibrantly coloured and possesses an undulating kinetic energy, but it is the subject matter which leaves the greatest impact. In one panel, three small white crane-like birds are huddled in a nest, while a more mature and elegant bird looks on. In another panel, a different older white bird prepares to fly away. The final panel focuses on the flowers and plants surrounding the nest. The painting depicts the artist’s very personal struggle over the custody of her children with her late ex-husband, and holds a very special place in her heart.

As a mother of nine, a grandmother of 21 and a great-grandmother of 17, family plays a key role in Kartika’s life. It is her gratitude for the health and happiness of her children which spurs her charity work. She founded her first school for handicapped children in 1963, where she taught painting. She now has two schools and is still very active in her charity work. For her visit, Kartika has planned to auction off two of her live paintings that she will create in Singapore to raise funds for charity. She hopes to create one of the live paintings together with children.

Kartika is based just outside of Yogyakarta and has lived there for most of her life. She arrived in Yogyakarta from West Java with her parents, along with other artists who, with the support of Soekarno and the Sultan of Yogyakarta, made the city their home. Kartika reflects that the younger generation of artists in Yogyakarta are lucky to have access to an art school, art materials, and the opportunity to be invited to overseas exhibitions.

Wrinkling her forehead, she tells me of a recent encounter with a young art student who had asked her whether artists of her and her father’s generation needed to drink alcohol before being able to paint. “That means that he must drink [alcohol] before he can paint. He must be drunk first,” she clarified, her disappointment palpable.

She shakes her head in dismay, and laughs as she tells me how artists were so poor in the past that most of them could not afford food, let alone alcohol or paint. From having to exchange one of her father’s paintings for food from an Australian army official, to travelling to Singapore on the deck of a boat in 1949, Kartika truly has had a lifetime of experiences behind her. When asked about what she hopes her legacy to be, she thinks carefully before speaking about being a female artist, and the strength that women possess. It is clear that one of Kartika’s greatest legacies will be empowering other women, artists or not, to be independent and to do what they truly love.

As I wrapped up my interview, I finally plucked up the courage to ask Kartika about ballet classes at the Affandi Museum. Her face lights up, and she smiles with such love, “Yes! (The teacher was) my daughter. My oldest daughter Helfi.”

What a moment – to have first been introduced to Affandi and Kartika’s works as a child heading to the museum to dance, and now to be interviewing Kartika herself 24 years later! It is as if I have come full circle, and life is reminding me that everything happens for a reason. The poignancy of this moment, in the presence of this strong, positive and talented individual, makes me feel as if I could do anything.

_____________________________

The exhibition “If Walls Could Speak” runs from 1-11 February 2020 (open daily from 10 am-10 pm) at Ion Art Singapore and features 30 artists from around Asia, divided into The Masters, Emerging Artists, Established Artists, and Singapore Artists.